BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

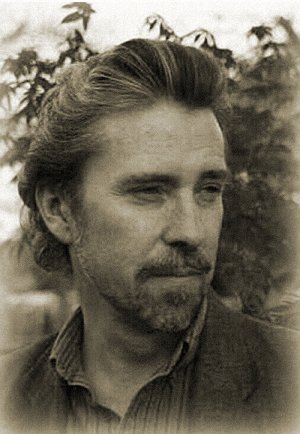

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Disappointing George News Copyright © 2018 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

disappointing george news

Published in Black Static #62, Mar-Apr 2018

Everyone loves having a great story to tell.

I grew up in what was then known as (and perhaps still is) a 'mixed neighborhood', meaning different ethnicities, in my case Irish-American, Italian-American, African-American.

When I was a child, my best friend was a black kid named George. We were inseparable, as childhood pals often are, like the Edgar Allen Poe story The Purloined Letter, where two men are so comfortable in each other's presence they can sit next to each other without the need to say anything. "For one hour at least we had maintained a profound silence...For myself, however, I was mentally discussing certain topics which had formed matter for conversation between us at an earlier period of the evening." Makes you realize just how great a writer Poe could be, that he could see and convey that specific idea.

We'd go up into the woods behind George's two-story house each mysterious Summer day, tickings in the trees, blindness in the sky, leaning against boulders, pulling off and eating wild blueberries from the bushes reaching towards us, fingerpads smudged purple, talking about everything, and isn't it true that some of the most honest, most unguarded conversations you have in your life, you have as a child? You rarely find that honesty again as an adult, in others or yourself, except in special circumstances, such as when a couple breaks up late at night, black windows, naked legs, ice cubes in a tall glass, hurtful words, exhaustion.

George became my first writing collaborator. We were going to write a novel together called, The Executive. We were twelve. The Executive was going to be about a young powerful man in the business world who got anything he wanted, including women, and never had any worries. Again, we were twelve. I have no idea where the hand-written pages of those first few chapters are now, although I would absolutely love to read them again, at the other side of my life, just to get a 'you are there' glimpse into who I thought I was way, way back then.

We'd go to Saturday matinees together each weekend, an island with palm trees after the long swim of a school week, always a B horror film. One early evening we were sitting on the curb of a sidewalk, sneakers in the street, and George asked me if I were more afraid of Frankenstein (meaning Frankenstein's monster), or Godzilla. A serious question, so I gave it serious thought. "Godzilla. Because I could outrun Frankenstein, but I could never outrun Godzilla." George had a different answer. Frankenstein. If Frankenstein were chasing him, he could outrun him, but Frankenstein would keep coming, and eventually George would get tired, run out of breath, and wouldn't have enough strength left to crawl away as Frankenstein lumbered up to him, bent over. But if it were Godzilla, that skyscraper-sized lizard would just crush him with its foot, and it'd be over with in a second.

As we grew up, as often happens, we drifted apart. Pals who saw each other less and less. I got a job in Manhattan, George got a job locally. A few years passed. When I was in my late teens, I was driving down Boston Post Road in Greenwich one afternoon, and off to my right, I saw George on the sidewalk. Honked to get his attention.

He ran over through traffic, swung open the passenger side door of my VW bug. He looked different. George, but bigger, less innocent. His eyes had changed. As had mine. "Are you having sex with girls?" "Yeah." "Do you like to get high?" "Sure." I agreed to stop by his family's home later that evening.

I had known George's family for most of my childhood. Watched TV in their living room, had dinner at their table, went to church with them a few Sundays. His mother, and his sisters with their weirdly-shaped eyeglasses, seemed happy to see me. "George needs you now, Bobby."

Up in George's room, door shut, we smoked pot. Listened to The Rolling Stones' latest album, Let It Bleed, on his turntable. "If you were guaranteed an absolutely dependable supply of heroin, at no cost to you, would you start shooting up heroin?" I thought about his question, stoned. "No." "No!? But it's an absolutely dependable supply!" That night is the last time I ever saw George.

A few years later, I moved to California. Years and years after that, Mary and I were living in Texas, and I heard George had died from a heroin overdose in Harlem.

I felt really bad. George had finally run out of breath, Frankenstein's monster following him, getting closer, too close, bending over as my childhood friend dropped to the sidewalk. White foam on his black lips. I posted a blog about our friendship, his death.

A few years after that, I got an email. From George. He didn't die from a heroin overdose in Harlem. He was alive, living in Maine, with a wife, children, and grandchildren. So at the end, I lost my great George story.

In a 1956 interview with Paris Review, William Faulkner said, "The writer's only responsibility is to his art. He will be completely ruthless if he is a good one…Everything goes by the board: honor, pride, decency, security, happiness, all, to get the book written. If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' is worth any number of old ladies."

When Faulkner spoke about robbing his own mother, he was, of course, speaking metaphorically. We're not going to literally knock out our poor, dear mother with a jaw punch and root through her old-fashioned, oversized purse, pulling out crumpled Kleenex looking for folded currency, but we are going to take aspects of her we've observed over the years, events and mannerisms, and use them in our stories in a way that might be considered cruel, if she were to ever recognize those aspects of herself in one of our characters. We do that with everyone we know.

No one in the vicinity of a writer is safe. Because a writer-a good writer-is willing to get to the truth of any character. And that embarrassment comes from all the people the writer knows, including-most importantly-the writer himself or herself. Because if a writer is not willing to write unflatteringly about themselves, to be that honest, they are not a writer.

I remember reading once in a newspaper about a woman who was doing her laundry at home, she opened the top lid of the washer to add another item of clothing while the drum was chugging, pushed it down into the swishing soapy water, and the strap of her bra (apparently she wasn't wearing a blouse) snagged on the drum, the chugging of the drum yanked her further down into the washer, and during that disorientation, held down, the steady back and forth rotation of the drum against her head beat her to death. That death so impressed me-the absurdity of it-I included it in one of my currently unpublished stories. And I feel so sorry for her children, having to recount the circumstances. "Your mom died? Oh my God, I'm so sorry! What happened?"

When George does eventually shuffle off, it's likely he, like I, like you, will die from an event far more boring. Cancer, uncooperative heart, indifferent kidneys. Which won't be as interesting to write about.

I'm absolutely joyous to have found out George is still alive, I guess, but as a writer, it would have been so much better if in fact he had died of a heroin overdose in Harlem, it was such a great story, and in that sense, the news of him still being alive, playing with his grandchildren, is very, very slightly disappointing.