BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

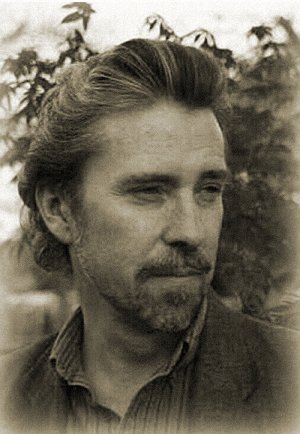

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

All Reassurances Can Be Peeled Away Copyright © 2018 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

all reassurances can be peeled away

Published in Black Static #64, Jul-Aug 2018

I saw Psycho with my parents when it first came out. I was nine years old. You might think it odd that parents would take a young boy to see that movie, but the truth was, at that time, during its initial release, no one knew anything about the film. Hitchcock had mostly made thrillers up to that point. And Psycho seemed like it would be another thriller. A woman embezzles $40,000, runs away to start a new life with her lover. Familiar Hitchcock territory. So much so that when Marion takes a shower, and through the translucent shower curtain we see the bathroom door silently swing open and a shadow enter, most people in that audience from almost sixty years ago chuckled in their comfortable seats, assuming it was that shy motel clerk about to make an amorous move, but then, as that flimsy curtain was yanked sideways, and a long knife raised above the wetness of that bare, unprotected body, people screamed, stood up out of their seats, gathered out in the aisles, holding onto each other. It was like they had witnessed a train derailment. Never before had the protagonist in a movie been killed in the first third of a film. And that was Hitchcock's brilliance (Wes Craven paid a homage to that scene thirty-six years later, when the seeming protagonist of Scream is murdered early in the movie.) We all thought we knew what was going to happen. Because that's the way it always happened before.

The company I worked for was bought and sold a number of times over the years. Each transfer of ownership, more and more of the people I saw every day sipping coffee in a break room, relaxing, were shoved out the airplane's slid-open side door. White clouds, blue sky. No parachutes. Hundreds tumbled in the air down towards the indistinct green land masses of worker's comp.

The most recent time the company was acquired, I was told I needed to catch a morning flight from Dallas up to Columbus, Ohio, about a thousand miles away, to deliver a speech in front of a large crowd of the acquiring company's salespeople and executives, in a hotel ballroom a ten-minute taxi drive from the airport. If my speech was a success, I'd continue working for the new company, and in fact would gain a more influential position. If my speech was a dud, I'd be shoved out the airplane's side door like all the others.

Arriving in Columbus on a Wednesday morning in my dark suit, catching a cab, talking nervously to the driver, passing by all the uninteresting buildings in Columbus, block after block, arriving at the hotel just before lunch.

The moderator on the stage at the front of the hall, announcing me, beckoned with his raised right hand for me to come down the aisle, step up on stage, walk across the stage to the speaker's podium.

The worst part, of course, is when you face forward in the bright lights, seeing the large crowd seated in front of you. I had absolutely no idea how my speech was going to go. If it would be spectacular, or a disaster. I leaned into the microphone. Opened my mouth.

After Mary and I explored Alaska for a couple of weeks in our 1989 three-month road trip across North America, me staring from the steering wheel out at the open road in front of us for eight hours a day, coming up with more scenes to use in my next novel, Father Figure, we headed back down through Canada towards the United States. Our first night returning, we stopped in Destruction Bay, a small community of about sixty inhabitants on Kluane Lake in the Yukon. Secured lodging for the night. A small TV in our room, the one channel showing an old black and white movie in French. Once we got in bed, turned off the light, and there was that deep country silence that exists outside of cities, we heard drums start up in the hills surrounding Destruction Bay. Drums rhythmically smacked not with sticks, but wrinkled palms. I heard Mary's lovely voice in the darkness next to me in bed. "So…kinda creepy?"

The drums went on for about half an hour, up and down the dark hills. And then stopped.

A few breaths after the drums finished, howls started up, from all over the hills. The howls of wolves. And as frightening as those howls were, from wild animals that could never be petted, they were also beautiful in their individual voices. The howls lasted for hours. No one knew where we were. A thousand miles away from anyone who cared about us. We watched the one dark window in our hotel room throughout the night, and didn't sleep.

Some people find the ending of Psycho disappointing. Marion's lover, her sister, and the local sheriff sit in a room in the county court house while a psychiatrist who has examined Norman Bates gives a detailed explanation as to why the shy motel clerk assumed the identity of his mother, and committed Marion's murder. The explanation is heavy on exposition, and neatly ties up all loose ends of the story. It's the 'scientific' explanation for what happened. But what makes Hitchcock's film so perfect, and truly frightening, is that the next scene undermines the pat conclusions reached by the psychiatrist. We see Norman in a strait-jacket, sitting in a chair, his mind dominated by his mother, insisting she's innocent, that she wouldn't even harm the fly buzzing around his/her face. And as Norman raises his face, we see a smirk, first in his lips, then in his eyes, and we realize whoever Norman is can never be explained by science. Norman is a work of Art. Unknowable.

Mary and I survived our night on Destruction Bay. Were we in fact in danger? Or was this just a routine night in Destruction Bay? We don't know. Nothing is known.

I thought poor Marion would survive until the end of Psycho, because the protagonist always had before. I thought I would survive any cut-backs at work, because I always had before. I thought our stay at Destruction Bay would be fun, because our stay everywhere else had been before.

My speech in Ohio went really well. The Senior Vice President of my division made a point of standing up out of his chair after I finished, clapping loudly, looking at me from the back of the hall, raising a right thumb up into the air. So I kept my job. In fact, got promoted. More power, more money.

A month after I flew back down to Dallas, telling Mary about my promotion, and we celebrated with really big lobsters, red from the steaming pot, my company moved into a new building. Most of the remaining workers were assigned cubicles. A few of us got offices. Each office had tall glass panels on either side of their door. As those of us who had been granted offices walked down the carpeted hallway, seeing where everyone was relocated, we noticed that in the left glass panel beside each office's door, the occupant's name was etched in the glass. Bill, a tall gay guy with a pale moustache, turning around from his etched name, put his hand over his heart. "So that's some reassurance, right? They've etched our name in glass?"

He entered his new office for the first time, turned around to look at the etching from behind, reached forward, touched it.

Pale mustached face looking up. "Guys, our names aren't etched in glass." He peeled his etching off the glass side panel. "They're fucking decals."

Within a year of that day our small group toured our new offices, discovering the decals, everyone in that group except me was let go. Within two years of that day, I was let go. Tumbling down through the white clouds, blue sky.

All reassurances can be peeled away.