BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

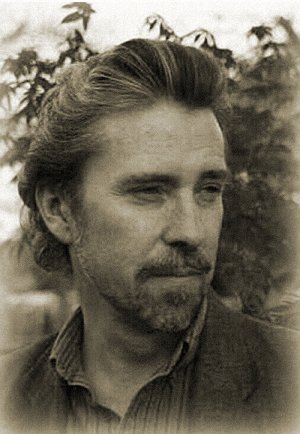

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2012 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to marginalia.

interview

Midnight Street was my first interview.

Over the years, Trevor Denyer has been the editor who is the most receptive to my fiction, for which he has my eternal gratitude. I first began publishing with him in his magazine ROADWORKS, starting with my story "Rump-a-Thump" in the Summer 2000 issue. After that he published "Visibility" and "Fish" in the same magazine. When ROADWORKS folded, I began appearing in his new magazine, Midnight Street. Over the course of its run, Midnight Street published some of the best stories I've written: "The Machine of a Religious Man", "Fleeing, on a Bicycle with Your Father, From the Living Dead", "Rocketship Apartment", "Nobody I Knew", "Suddenly the Sun Appeared", and "They Hide in Tomatoes". Midnight Street (which is currently on hiatus) has always had a reputation for publishing fiction that strays from easy classification, which made me proud to appear in its pages. Trevor is one of those rare editors whose suggestions are always smart, sensitive to the story, and spot-on. They confirm my long-held idea that the best editors are also great writers.

This interview first appeared in 2006 in Issue 7 of Midnight Street. It is republished here with the permission of the editor.

Tell me about yourself. What do you do for a living (apart from writing)? What's it like where you live? Tell me about your family.

I'm married, have been for a quarter of a century, no children but seven cats. Mary and I live in a two-story red brick house in a relatively small town (30,000) about half an hour south of Dallas, Texas. We have goats for neighbours, bird song instead of car alarms. We spent a decade driving around America, living here and there, but as we got into our late thirties we realized that as much as we enjoyed the road, the excitement of "a new career in a new town", we wanted to settle down. Texas, with its big blue sky, its friendly people, turned out to be the perfect spot to unpack permanently.

Like a lot of writers, I thought of any job I held to pay bills as unimportant, not my "real" job, so I tended to just fall into different occupations, rather than plan any sort of rational career trajectory. As a result, I spent quite a few years working in a bank, as a teller, in Connecticut and California, then when I tired of that, I switched to health insurance (processing claims) when Mary and I moved to Maine. When we left Maine and eventually wound up in Texas, I found a new claims processing job, but one day made a wish, a rather fervent wish, that I be able to support us full-time by writing. Around about the same time, I applied for a job composing the health benefit booklets people receive when they start work with a company, and got hired. It wasn't until a few months later that I realized my wish had been granted, but not the way I intended. I should have specified, be able to support us by writing, yes, but by writing fiction, not health benefit booklets.

But it was too late.

Writing the benefit booklets though, and the legal writing I eventually moved into, drafting contracts, was interesting, because the type of writing you do for both functions is the exact opposite of what is considered "good writing". The benefit booklets, for example, a form of technical writing, relied, like most technical writing, on the passive voice. A no-no voice if you're writing a story (Jane always "throws" the ball, the ball is never allowed to be "thrown by" Jane), but really the best voice if you're explaining something in a manual. Similarly, although creative writing avoids repetition (if the river Brad jumps into is frigid, the drops of water he shakes like a dog out of his hair, climbing up the bank, better be "cold" or "icy", anything but "frigid" again), legal writing depends upon repetition. If you talk about a "covered person" in one provision, you can't use "participant" in the next section, even though both terms mean the same thing, because the mere fact you chose two different terms can be interpreted in court to mean you're referring to two different entities.

As the nineties went on, Mary and I, who previously had no real interest in business, rose within our separate companies to where we both reported directly to the presidents of those companies. As a teenager, I would sometimes try to project myself into my future, picturing me in an office, wearing a suit, because that seemed to be the adult world, but I could never make it seem plausible in my mind. When it did happen, I found out I actually kind of enjoyed it. In 2000 I worked out a deal to be able to work from home, telecommuting over the Internet, while Mary continued to work in the city.

One day in April, 2002, giving the cats their noontime meal in our kitchen, getting ready to sit back down in front of the computer, I got a call from one of the women on Mary's staff. She had gone into Mary's office to take Mary to lunch. Mary was sitting in her swivel chair, unmoving, staring straight ahead. She had had a stroke. As it turned out, a severe stroke, with a clot in her brain the size of an egg.

Our life together had been spotlessly happy, not a care in the world, and then suddenly, out of the blue, that phone call.

I spent the next nine days in the intensive care unit at the hospital, holding Mary's hand, encouraging her to try to move her right toes, to try to remember her name.

Mary's recovered significantly in the four years since, thanks to years of therapy and her own willpower. She can walk, climb stairs. Because of the intensity of her stroke, she suffers from a condition known as aphasia, the inability to understand language (her stroke, like most left-side strokes, destroyed large sections of the speech center in her brain). The best way to understand the effects of aphasia is to think of a time when you were trying to remember the name of an actor, but the name stayed on the tip of your tongue. With aphasia, that elusiveness is the way it is with every word in the English language. "Garage" has become "the car place", or, on some days, just a finger pointing at the front of our home. But with love, and a lot of humor, we've both emerged from what happened, and we're happier now than we've ever been.

Why do you write? What successes have you had in the publishing world? How long have you been writing?

Why do I write? The honest answer is, Because I have to. I know writers often give that answer, and I hesitate to because it makes me sound like I'm trying to portray myself as some tortured, romantic figure, but really, I do have to write. The thing about writing is, it requires an extraordinary degree of concentration, and there's nothing else in my life that requires that degree of concentration. I like being in that state of extreme focus, where the arrangement of words means so much. It's like taking a drug, except you don't need to make small talk with a dealer, and you can't be arrested. Writing is also a great release for me, allowing me to work out issues in my real life in an imaginary world.

I've had some success in the publishing world, more so each year, but not as much as I'd like. A lot of the stories I write really don't fit a specific market. Genre magazines often don't want my stories because they're not strictly horror, whereas a lot of literary magazines think my stories are too odd. But I don't mind. I decided long ago to simply write what interests me. Some of my favorite stories have never been published, and probably never will be. If years go by and I'm unable to sell certain stories, I'll just post them on the Internet, on my website. That's the great thing about the Internet-- you can be your own magazine. One of my best successes in publishing was getting my novel Father Figure published as a trade paperback. The company has since gone out of business, so now I offer the entire text of the novel on my website as a free PDF download. It's been downloaded over two thousand times in the past few months. On the other hand, my other two novels, Kid and As Dead As Me, remain unpublished.

I've been writing since I was a child.

How easy (or otherwise) have you found it to get your work published? Have you found particular themes or styles of story work better than others and are easier to sell?

As I've gotten more recognition, I've found it's easier to get editors to look at my stories, though not necessarily publish them. Without question, the easiest type of story for me to sell has been a story with strong horror elements. There's an established market. Stories under 5,000 words are also a lot easier to sell than longer works, since an editor reasonably wants to include as many stories in an issue as possible, but I often wind up writing 10,000 word stories. Sometimes I feel like telling my characters, "Don't talk so much! Get to the next scene! We're over our word budget!", but they don't listen to me.

What do you know about the independent press in America? Is there more opportunity than, say, in the UK?

I actually have some knowledge here, since I'm a submissions editor for the American magazine Lullaby Hearse.

There are some magazines in America that welcome the off-beat story-- I'd point to Lullaby Hearse, and a few others-- but generally, I think UK magazines are more willing to look at a story for its literary worth, and to publish the "square story in a round hole". There's no equivalent in America, for example, to Midnight Street. The UK small press seems to have a greater willingness to consider the unclassifiable story. At least that's been my experience. America has an enormous pool of university-based magazines, but most of these are rather timid about what they accept. There's been an unfortunate tendency in the university press over here to favor polite stories.

You must be very pleased that 'The Machine of a Religious Man' which was published in Midnight Street # 4 is to be reprinted in the forthcoming 'Year's Best Fantasy & Horror' anthology. What inspired this story?

I am very pleased. The validation means a lot. A story for me usually starts with a single idea. An image, a character; sometimes just a line of dialogue. The trick is to be patient, let that idea grow in my subconscious, until other images or characters appear. When I get enough, then I go in and search for a way to connect all the dots. The Machine of a Religious Man started with the idea of men in a car, racing down a dark highway. Once I put Gordon in the back seat, crying, unable to speak, I had to come up with a reason why he was crying. The story grew out of that, the desire of a man to give up, end his life, he's had enough, but who, because of his moral values, couldn't bring himself to commit suicide, and so had to create an extraordinarily elaborate machinery of events which would allow him to die "by accident". It's a sad story, of course, but read a different way, it's also a happy story, in that it tells of a strong friendship between two men, Gordon and Bonay, and Bonay's willingness, despite his own reservations, to do what his friend wants.

What is a typical day for you? How do you organise yourself to write?

Our life has gotten much simpler since Mary's stroke.

Weekdays I go to sleep around nine, wake up at one, shift around in bed, left side, right side, stomach, fall asleep again around three, wake up at four, fall back asleep around five, wake up at five-thirty. I never get a truly good night's sleep anymore. Once I'm out of bed, Mary still sleeping, I go upstairs to my study, read my e-mails, print them, look at the overnight statistics for my website, read the Google news, during which time some of the cats have jumped up on my desk, rubbing their tails under my nose, reminding me their food bowls are empty. I troop downstairs, make coffee, feed the cats. Watch the morning news with the sound turned down until Mary wakes up. We have a cup of coffee together in bed, then I go upstairs and start my day job (at this point, twenty hours a week, four hours a day). I come downstairs at nine, having put in two of my four hours that day, walk down to our mailbox while Mary cooks breakfast. We eat in the bedroom, watching Will & Grace episodes we recorded. I go back upstairs, put in my remaining two hours, come down around twelve. At that point, we often go out into our backyard garden, a small green park with winding grass paths, fresh air, birds and squirrels, and work for a couple of hours.

At four o'clock in the afternoon we go upstairs to project. I write for three hours, from four to seven, usually turning out one story a month.

Sundays we watch DVD's we've rented through Netflix, and sometimes go out early in the morning to buy a huge amount of fast food we eat while watching the movies.

I actually am very organized when it comes to my writings. Each story starts as a series of blue-inked notes I write on torn-off strips from a yellow legal pad, then store in a 6 inch by 9 inch manila envelope. I shake out the notes once I'm ready to begin the story. When the final draft is completed, I place all the notes and early drafts in labelled folders in an accordion file, which is stored in one of several upright four-drawer metal filing cabinets. The accordion file includes all submission letters, acceptances, contracts, and copies of the work in print. I track which stories are out, where they've been submitted, the response, in a Word file I created.

Who do you read? To what extent have these authors inspired your own work?

I read very little now, because I just don't have the time. Mostly magazine articles, and non-fiction. The authors who have influenced me the most are Vladimir Nabokov, William S. Burroughs, Allain Robbe-Grillet, and Donald Barthelme. Each writer approached fiction in a different way. I've tried to incorporate those approaches in my own writings. Other writers I've admired are Julio Cortazar, who unfortunately has fallen out of favor, nobody knows who he is anymore; Phillip K. Dick; Richard Matheson; and the collective of writers who produced the Hardy Boys series under the name of Franklin W. Dixon. There was a Hemmingwayesque directness to their writing, whether describing an ice boat skinning across a lake, or the joy of waking up to the smell of frying bacon.

Do you attend any writers' conferences or gatherings? If so, have you met any well-known writers? Do you find it helpful to mix and communicate with other writers?

I've never attended a writers' conference. I'm not opposed to the idea, it just hasn't happened. The American novelist/essayist Gore Vidal once sent me an e-mail through an intermediary telling me he enjoyed my work, but otherwise my communication with other writers has been limited. I find it helpful to mix and communicate with regular people, I get a lot of my ideas that way, but I just haven't had an opportunity to spend any time with fellow writers.

What tips can you give aspiring writers?

To me, the most important tip is to be honest. Write what you yourself want to write, not what you think an editor, publisher, girlfriend, boyfriend wants you to write. Don't believe all this nonsense about story or character arcs unless you want to write a completely predictable, same as it ever was story. Walk away from people who tell you the key to writing a great story is, for example, to study chess. There is no key to writing a great story. If you feel it, your readers will feel it. It's got nothing to do with chess. Edit. That, to me, is the hardest thing to get aspiring writers to do. Clock how long it took you to write a story, versus how long it took you to edit that story. If you spent more time writing the first draft than you did editing that draft, you didn't edit it enough. No one ever created a great story through writing. They created a great story through editing. The aspiring writer's greatest enemy is laziness.

What are your future plans? What are you working on at the moment?

I just finished an 11,000 word story (there I go again with these completely impractical long, unmarketable stories) about the relationship between a daughter and her father over several decades (literary). I'm working now on a story about a man who has a disturbing encounter with an assertive woman (horror). I want to set aside time to write two novels, Just Like Furniture, about a man who was once famous and wants to be famous again (science fiction/horror); and It Hurts the City, about a man who is ruthless in the business world (science fiction).

Many thanks, Rob.