lately

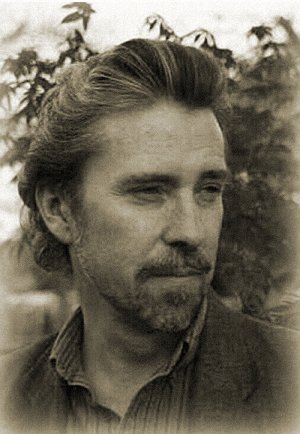

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2005 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2005.

bones bleed

Joe, Mary's dad, flew down from Milwaukee to spend the holidays with us, as always.

Christmas day, after our meal of prime rib roast, served later in the evening than expected, because the roast was seven ribs long, after Mary had gone to bed, planting sleepy kisses on both our shaven cheeks, Joe and I sat at the uncleared dining room table, finishing a bottle of red wine, tilting the bottom of the bottle way, way up, to get out the last crimson drops, alive with reflected candlelight, talking about this and that, deciding we'd talk longer, after we each used the rest room, Joe, the bathroom off our front hall, me, the bathroom within the downstairs master bedroom, me wandering through the brightly-lit kitchen to the dark slumber of the bedroom, passing Mary's exhalations, reaching out, in the darkness, towards mirrored closet doors, tiled shower walls, to tightrope to the toilet, when I heard a loud crash, Joe's voice rising from several doorways away. "Rob!"

I hurried back to the front hall.

Our dining room, where the three of us ate our Christmas dinner, is at the left front of our home. The dining room itself is octagonal, with a deep step down to the hard white marble tiles of the front foyer.

Joe, walking across the soft white carpet of the dining alcove, had clearly forgotten about the step-down.

He put the black shoe of his right foot forward without realizing the next step was six inches lower.

He tilted over, from that great height, crashing down on the hard tiles on his right side.

When I reached the front hallway, he was lying on the tiles of the front foyer, face twisted with pain. Joe is in his eighties. Both his hips have been replaced from previous falls.

I squatted down next to him, put my hand on his left shoulder to let him know I was there. "Joe?"

His face seized up.

I wanted him to say something, to make sure, first of all, he wasn't in shock. "Can you move your right arm?"

He exhaled, eyes blinking. "I don't know, Rob." A minute passed. He tried lifting his right arm, face compressing. "Ow!"

"Should I call an ambulance?"

Another minute passed, Joe breathing hard, lying on the foyer floor. "Let's wait."

I sat down on the cold marble tiles beside him, hand still on his left shoulder. Five minutes passed.

He tried sitting up. "Ow!"

"Do you want to sit up?"

"Yeah."

I grabbed him around his waist, swung him up so his back was propped against the front door.

He closed his eyes. "This is so…fucking…stupid."

I was concerned because he was on the cold tiles. The weather had been below freezing the past few days, and some of that frigidness had crept under the front door. "Do you think you can make it upstairs if I help you?"

"I don't know, Rob." He sat, back propped against the front door, for a while, eyes closed. Let out a sigh. "Let's try it."

I put my arms through his armpits, rose up into a stooped position, tried lifting him.

"Ow! Ow!"

I set him back down.

"Do you want me to call an ambulance?"

He shook his head. "Can you put me in a prone position? Maybe I'll sleep here tonight, and we'll see what it's like in the morning."

I dragged him over to the living room, getting him up on the white carpet. Dashed upstairs, pulled the blanket and comforter off his bed, brought them back down, tucked them around him.

"So fucking…stupid!"

I went back to the master bedroom, its closet, pulled a blanket off one of the shelves. Settled across one of the settees in the living room, still fully dressed, even to my shoes, within sight of Joe. Pulled the blanket up over my shoulders.

He nodded off, mumbling in his sleep, letting out Ows! every minute or so.

I kept an eye on him for an hour, smoking an occasional cigarette, wondering if indeed this was the best way to handle the situation.

He was obviously in a lot of pain. He was sleeping on the floor, not a good idea at any age, but certainly not a good idea for someone in their eighties.

Finally, I decided to wake up Mary, get her opinion.

I bent over in the bedroom, gently shaking her shoulder. Her eyes popped open.

I waited until she was fully awake. Asked her to sit on the edge of the bed.

"Your dad is fine. But. He fell in the front foyer. He's on the living room carpet now, trying to sleep. He can't get up. I think he broke his right shoulder."

We both went out to where Joe was mumbling in his sleep.

Mary woke him. "Dad? Dad? Are you okay?"

The three of us talked for a minute, decided we should call an ambulance.

I dialed 911.

A woman's voice came on immediately. "What's your emergency?"

"My father-in-law fell about an hour ago. He's still on the floor. I think his right shoulder is broken."

After I hung up, I gathered up our seven cats, shut them in different upstairs and downstairs rooms.

In the distance, I heard the wail of an ambulance. Who would think Christmas Day would end like this?

In the half moon window above our front door, I saw green and red lights revolving.

I opened the door, letting in the cold night air.

An ambulance was parked in our driveway, men unbolting its back doors, pulling out equipment.

A moment later, there were three male paramedics in our front foyer, radios on their belts hissing and bursting with static, short inquiries.

I have to say, I was impressed with their professionalism.

One of them bent down over Joe, looking into his face to assess his mental state, while another, standing with a clipboard, asked me Joe's name, which I gave as Joseph Meier, and got the details of the fall from me.

The one bending over Joe asked him to try moving his arm.

"Ow! Ow!"

"I'm going to cut open your sleeve with a pair of scissors. Is that okay, Joseph?"

Joe nodded, fully alert.

The paramedic on the floor cut up Joe's gray shirt sleeve, to his shoulder. There was a long, dark bruise on his upper arm.

He felt along Joe's arm, his shoulder, then asked Joe to move his right arm in different directions. Some directions caused no pain, others, a lot.

"I think you've got a broken right arm, Joseph, up around the shoulder. We're going to have to take you to the emergency room. Is that okay with you, Joseph?"

I felt like I should say, his first name, officially, is Joseph, but he goes by Joe. But I didn't want to distract anyone.

Now that the urgency of establishing Joe's condition had been completed, there was a more relaxed period of waiting for the portable stretcher to be brought out of the ambulance, wheeled up our driveway, through our front door, clacked down so Joe could be lifted and placed on it. Once he was secured, canvas straps tightened across his body, one of the technicians asked me what hospital he should be taken to.

I chose the nearest facility.

Mary and I walked alongside the stretcher as it was rolled to the open doors at the rear of the ambulance, its revolving red and green lights, incongruously, evoking the Christmas season.

Mary and I followed in our car behind the ambulance on the dark highway lanes.

Once inside the emergency room, I explained at the counter we were here for Joseph Meier.

"The gentleman who broke his arm?"

"Right."

She told me the room number, buzzed us through.

A male triage nurse was with him already in his room, calling him Joseph, gently folding back the material of his scissored sleeve to look at his arm, leaning forward, touching the purple skin.

Another male came in, with a clipboard, to get Joe's insurance information. I had grabbed Joe's wallet before we left, flipped through it now to pull out the necessary cards.

Joe wears a hearing aid, which Mary brought with her. She handed it to me. I put it in my sports jacket side pocket for safekeeping.

I had a stomach flu from earlier in the day, manageable but bad enough that we had skipped going to Christmas mass. I felt it coming back, so once I was sure the hospital had all the insurance information needed, and that Joe was receiving proper attention, I excused myself, trotted to the nearest bathroom, threw off my jacket, draping it across the wash basin, and was sick.

After a few minutes I felt much better. I put my jacket back on, returned to the examination room.

Mary told me Joe had been wheeled out for x-rays.

We sat side-by-side in the empty room, waiting for his return.

Once Joe was back, the emergency room physician, big as a football player, told us he had examined the x-rays, but couldn't find anything broken. Using his fingers, he probed Joe's right arm, shoulder.

Joe cleared his throat. "I'm really in a lot of pain. And I can't lift my arm to the side." He tried, to demonstrate. Winced.

The physician nodded. "Let me look at the x-rays again."

He came back in twenty minutes. "Well, you're right. There is a hairline fracture at the top of your right arm, where it goes into the socket."

I asked about Joe's upper arm, heavily bruised, almost black.

"That's consistent with a fracture. Bones bleed."

Because Joe's fracture was hairline, a cast wasn't needed, just a sling. "The good news is the arm hasn't displaced." (It took me a moment to remember that 'displaced' is medicalese for 'dislocated'.)

On the way back from the emergency room, Joe, sitting next to me in the front passenger seat, Mary in back, asked if I had his hearing aid.

"Yeah. It's in my pocket." I drove another highway mile, then thought I'd better check to make sure it was still there.

It wasn't.

I kept driving, the car passing under the tall, bright highway lights. Reached into my right jacket side pocket again. My left side pocket. My inside pocket, scrunching my fingers down past the wallet and checkbook packed in the pocket.

Shit!

"Joe, I hate to say this, but I don't have your hearing aid."

"Say it again, Rob?"

"JOE, I'M SORRY, BUT I DON'T HAVE YOUR HEARING AID. I HAD IT EARLIER, BUT APPARENTLY I LOST IT."

He took the news with his usual good humor. "Oh, well."

I realized I must have dropped it in the confusion of the emergency room, maybe when I threw my jacket over the wash basin in the restroom.

I felt absolutely awful. Here Joe has a broken arm, causing him immense pain, and on top of that, I lost his fucking hearing aid.

I called the emergency room as soon as we arrived back home, but the hearing aid hadn't been turned in. I called again the next morning, but it still hadn't turned up. A few days later, when I had to drive out to the hospital to pick up Joe's x-rays, to deliver to the orthopedic specialist we were taking him to for follow-up care, I swung by the emergency room to inquire in person if his hearing aid had been found.

No.

Once we got home, Mary and I helped Joe upstairs to his room, made sure he had everything he needed.

He sat down backwards on the edge of his bed, gingerly pulled his legs up onto the mattress. There was no question of him changing into pajamas. He'd stay in his pants and cut-up shirt. "I may sleep sitting up. I think it'll be easier." Mary put both pillows behind his back, helping him settle against their softness.

Mary and I went downstairs, letting the cats out of the rooms in which I had shut them, both of us yawning as we made our way to our own bedroom.

I got up a couple of times during what remained of the night, tip-toeing upstairs, floating quietly to Joe's room at the end of the hallway, slanting my upper body in past the doorframe to make sure he was all right. Each time, he was sleeping, and this is the perfect word for it, "fitfully".

The next morning, Mary and I sat at our black breakfast nook table, drinking coffee, looking out at our winter garden, waiting for Joe to wake up. I remarked there weren't any birds at the feeders.

"They're at church."

"That's probably true. I'm sure if we parted the branches of the nearest hedge, we'd see all the birds inside, sitting on the branches. At the front, a bird nailed to a cross."

Mary laughed.

One of our cats, Beauty, black with green eyes, jumped up on the black tabletop, started padding around, snaking over to within my reach, my right hand rising to pet her, unbending my elbow to keep my scratching fingertips on the fur of her back-and-forth spine, struck again by the shyness of our pets, how they rarely look us in the eye.

I got up to urinate, standing over one of our toilets, still half asleep, trying to remember if this is the toilet that occasionally overflows, or the toilet that won't flush, or the toilet that works perfectly, when I heard Mary call me.

Joe had worked his way downstairs, blue bathrobe draped over his shoulders like an exiled general.

Despite his ordeal, he was in good humor, accepting this latest fracture in an admirably casual, non-complaining way.

We decided to have Eggs Benedict for breakfast.

While Mary poached our white and yellow eggs, Beauty banged her furred forehead against the squareness of my knuckles, the fingernails of my right hand lifting, scratching absently the top of her bobbing head, scratching the intimate knowledge of God locked in her little warm head.

Yesterday, the last day of the month, during a cold, drizzly morning, I walked down to our mailbox to mail the Netflix DVDs we had viewed over the weekend, and to get our mail.

Inside our box, snuggled with the usual bills and catalogs, was a thick white envelope from Social Security.

As I mentioned in the most recent Lately, we appeared before a judge in December, appealing Social Security's denial of Mary's application for disability benefits (Mary had a severe stroke two and a half years ago, and as a result of that stroke, has lost the ability to understand language, a condition known as aphasia).

We were hoping the court would overturn Social Security's denial, so Mary could start receiving disability benefits.

Mary was in the kitchen. I showed her the envelope. Her eyes widened. "Would you like to open it?"

She shook her head. "You."

I flipped the envelope over, slid my thumb under the sealed flap. "No matter what it says, we'll get by."

"I know."

I tore my thumb down the length of the flap, pulled out all the tri-folded sheets of paper.

The cover letter was on top. I scanned it quickly. There it was, in bolded print.

Notice of Decision - Fully Favorable.

I gave her a kiss. "You've been approved. You won your appeal."

Mary's shoulders went up. "I did?"

So that's a big, big load off our minds.