lately

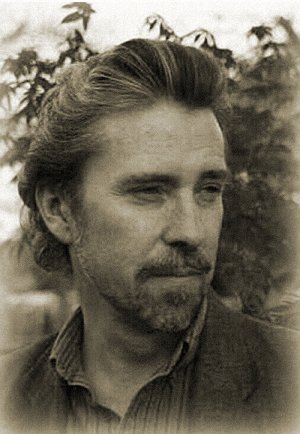

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2001 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2001.

photographing time

Back in 1987, when Mary and I were living in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, just a sneer away from Portland, Maine, Maine being a state we had moved to five years previously, from California, we were sitting around our kitchen table, it was night, it was a Tuesday, it was snowing outside our third floor apartment, white wind brushing against the dark panes of the window above our aluminum sink, when we decided, seated, talking quietly in our pajamas, to buy a camcorder for our upcoming leave of the state.

We moved to Maine because I grew up in New England, Connecticut, and we thought that Mary, a California native, might enjoy living in a land, and I might enjoy returning to a land, from my six years in California, where the changing of the seasons is more dramatic.

Once we got to Maine, in 1982, we realized we had traded green surf and jade palm trees for yellow snow. We almost immediately plotted our lift-off to somewhere better, but the fuel for that ascent, money, took five years to raise.

A few evenings after our decision, after one of those silent marital conversations held in public using only our eyes (Yes? No?), we bought our camcorder from a boomingly cheerful, middle-aged salesman at the J.C. Penney's in Portland. In the years since, we've used this same camcorder, still reliably turning out high resolution videos, dust and sunlight still showing on window panes, to do video diaries of our life together, one new tape per year. We have tapes for fourteen years so far.

The initial entry of our diary, shot from below, shows my forward-tilted face looming in the upper half of the screen, full of vertical distortion, frog eyes peering down into the camera lens, my big lips proclaiming, "I can see a red light."

The great thing about camcorders, like the great thing about Polaroids before them, and a decade later digital cameras, is that they're private. Before, after you captured an image, you had to go to a stranger to have the image rendered. Now, you could photograph anything you wanted, and no one except me and you saw the result. Citizens could finally attain the most desired state of all in the technological world in which we now live, not fame, but anonymity. Camcorders became one more step towards personal freedom, and with it, personal expression. The revolution this time, and it was a significant revolution, came not through rhetoric, but through engineering.

What was captivating about the camcorder was that it allowed you to record your life. Not just the weddings and backyard barbecues, seated people waving at the camera, but the most mundane of all moments. Here I was opening junk mail, uncapping another beer, having to relight my cigarette. And here comes Mary, turning on the faucet over the sink, pinning back up on the wall the calendar that slipped to the floor, swinging open the door to the refrigerator.

Having the ability to record any moment from one's life, we became more conscious of how much of our lives went unrecorded. I can't tell you how many times, during those first few years, when I wished the camcorder were running. Us sweeping through the supermarket, pushing the aluminum-wired cart, discovering in the middle of a hushed, private conversation a new vegetable in the bins. Our late night conversations, so heartfelt, moon in the window, one or the other of us standing up to dump out the ashtray. Mary's smile, curved inward, at one of my words. Me trying to catch, as it fell out of my hands, fingers quickly scooping down the fronts of my legs, an opened container of greek olives.

Being able to record all these unique moments, but not, letting the best of our lives together go undocumented, entrusted only to memory, reminded us of the fleeting nature of experience.

We adjusted. We accepted that those best moments of us, and there were hundreds of them, would live on only organically, in our shared memory, otherwise unreplicated.

There is a desire to add significance to one's life. A personal moment becomes important because it's been preserved.

That record-keeping, whether image, word, or sound, can become the greatest defense against the indifference we all inkle. My life is not meaningless, because parts of it are on a shelf.

I've tried to preserve the glory and explosion of my life by writing. Sometimes I feel the more imaginary characters I create, the more real I will be, like a hard white seed in a moist section of orange. Oscar Wilde said of Turner that after you have seen a painting of his of a sunset, you can never see a sunset again except through Turner's eyes. That's for which I strive: that my description of a facial expression, a mood, a gesture, might so embed it's always summoned, even without proper attribution, each time someone "knocks like a cop" on a door, or sees the early morning sun stream through window blinds, "turning the rooms into lined paper."

If I will not survive, and of course I won't, at least a thought of mine will, like a clear bottle bouncing on the waves.

Lately, I've tried to impose my thoughts through images, rather than words.

Taking pictures is extremely rewarding, and extremely frustrating.

Stupid as I am, I managed to nonetheless instinctively know that the best way to start snapping the world was to choose stationary landscapes, walk backwards until each pasture was in the middle distance, frame the shot in the viewfinder, and press a button.

As I progressed in my photo-taking, to the modest degree I have, I realized I could probably take literally hundreds of pretty pictures. Indeed, each day I saw plenty of panoramas passively waiting for a flick of light. But each shot really would not look too differently from any other. They say naturally beautiful landscapes make the worse painters, because the artist does not have to exert himself or herself in the midst of all that splendor.

I wanted a greater challenge.

What I decided to capture was not so much the world itself, which lay patient and photographable, but instead the very fleeting nature of the world. A facial expression, the sudden, temporary lift of a bough into sunlight, the texture of food as it transforms during cooking.

I wanted to progress from photographing space, to photographing time.

My attempts so far have been a disaster.

I started off trying to photograph food as it transforms from a raw state to cooked. I wanted to capture that change of color, grey rising up to ruby, in the very fiber of the meat.

My first attempt, Lobsters, which is reproduced on this site under SENTENCE Photographs, Series III, actually turned out well (although everyone who mentions it refers to the lobsters as crabs, for some reason). Some of the side legs of the four potted lobsters have that raw, blue, briny color in their articulations, while other legs are clearly stiffening and reddening.

After that, I tried to capture a couple of fried eggs at the moment the egg white started turning from the color of thick water to a milk color. I envisioned an extreme close-up that showed the milkiness creeping into the colorlessness, two or three humped yolks, dark lemon-colored, imperious, still raw, riding above that flat transformation.

I took about twenty pictures while the eggs in the frying pan bubbled.

Not a one of them was acceptable.

For one thing, I was "racing against time." If an egg cooks, let's say, in two minutes, there may be a twenty-second window in which the egg is in that half-raw, half-heated state I'm trying to capture. That state can begin quickly, though, so I have to start photographing almost immediately. The problem I'm running into is that the camera I'm using, a Kodak digital camera (which I really like, by the way), can only take about six shots in rapid succession, after which it has to rest a moment before proceeding with single shots. The moment of transformation can occur during one of those gray, sunken gaps between button-depressability.

Even if I could take rapid-fire shots endlessly, though, another problem is that every shot I took was blurred. To me, there is nothing deadlier than a picture which is out-of-focus. If it's too bright or too dark, or not framed properly, I have a chance of fixing that. But if the resolution isn't there, the shine and crinkle of surfaces, there's nothing I can do.

After a while, I realized the bluriness was caused by my having lived such a pleasant existence, to where, after decades of drinking and smoking, and who knows what other enjoyments, my hands were not as steady as they were picking up a block with a purple letter W from the carpet. Mary suggested I use a tripod, which I positioned over a skillet, screwing it down to the proper height, to photograph lazily elegant slices of sirloin steak sizzling.

Voila! I had texture.

That took care of the problem of me moving while I was trying to take a picture, but it didn't take care of the problem of the subject moving.

Most of what I was photographing at this point I was photographing in extreme close-up, because that is where time fleets.

Wandering around our backyard, looking for something to photograph, I came across a upward-lifted sprig within the boughs of a blue point juniper.

A juniper is a conifer, somewhat similar to a pine tree in the structure of its branches. It has needles instead of leaves.

Deep within these patterns of old-growth, needled branches, a branch was sprouting new growth at its uplifted tip, the new growth a tender green the color of lime flesh, as opposed to the slightly darker, grayer green of the surrounding swirl of old-growth needles.

What a perfect image of Spring, I thought.

I maneuvered my tripod into place, focusing on the sprig.

But although my camera was rock-steady, the sprig itself was bobbing slightly in the backyard breeze, bobbing enough to blur when I pressed the camera's button.

I tried a couple of days, getting great detail and texture on the bigger, heavier surrounding branches, but still a bobbed blur on the sprig.

Today, the backyard was still. No breeze.

I set up my tripod again, aiming the tiny black square within the viewfinder directly over the sprig's delicate light lime shade of green, depressing the button a dozen times.

Mary downloaded the images from the camera for me.

Each image showed the motionless sprig, blurred.

Evidently, my new problem was what I suppose might be called a "nose effect". Even though I trained my camera's focus in extreme close-up on something that jutted out from its surrounding background, that background, quantitatively overwhelming, forced a refocus on itself.

Finally, here's a third frustration I'm having with taking photographs, which relates back to not videotaping all of one's life.

As I drive along, whether down a side street or highway, I'm constantly passing panoramas that are eminently photographable.

Sometimes I stop. Often, I don't. I forgot to bring the camera, I've already used up all my shots, the battery is low, traffic is too heavy.

But I always rue the ones that got away, much like I think back to certain suppers, or conversations in a hallway, or changes on a face, that would have been so easy to videotape, but which weren't.

My biggest fish that flipped away, no taste in its mouth of hook?

Mary usually drives by herself to work, but one day a week or so ago a fog rolled in before dawn, a fog the local weatherpeople called the thickest, densest fog that had come to this area in their memory.

I didn't want Mary driving alone in that, so I took her to work.

On my way back, the fog had lightened some, but was still thick, clinging to the first ten feet or so above the ground.

As I neared my exit, I saw across the green grass median that a cement truck had overturned, lying on its huge side across the opposite highway like a dinosaur, cab facing me. (No one was hurt, fortunately).

There was a perfect photograph. Amidst the swirl of fog, the bare discernment of the grey highway continuing down the green slope, at its front the big truck on its side, police cars pulled sideways around it, the red and blue flashes diffusing upwards into the fog, the cops out in yellow rain slickers, bare-headed, the ghostly green trees beyond.

It was an extraordinary image.

But I didn't take it. There was a lot of traffic behind me, there really wasn't much of a shoulder to pull off onto, the cops looked like they were down a cup or two of coffee. But I have to add, all these problems were minor. I could have pulled over, and I'm sure I wouldn't have been arrested for taking a picture. I didn't take it because I was afraid it wouldn't turn out well. It wouldn't capture the scene as I saw it, and afterwards, I'd no longer see that actual scene, only my recording of it, in all of its failed replication.

I have to content myself with having been given the opportunity to witness the visual grandeur of the accident, without preserving it. Except fleetingly, here.