lately

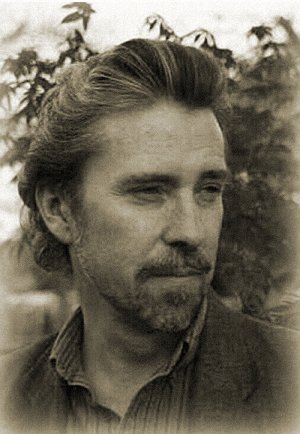

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2001 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2001.

i finish writing my fourth novel

I discovered I was a writer when I was a child.

It's a sixth finger or third testicle that once found, can't be undiscovered.

I've just finished writing my fourth novel, As Dead As Me, this week.

I feel depressed.

I always do once a novel is finished.

Writing a novel is different from any other type of writing. It's different from most other types of activity. Because of a novel's length, because you must sink down into its world, a world that evolves with your exploration, interior continents changing shape as you walk above the trees on sentences snapping up under your shoes as you write them, a novel tends to become a part of you. One of those periods in your life you look back on later and realize was not formless, but an episode, like taking a long journey, creating a garden, lying sick in bed through a disease.

As I neared the end, knowing more than my characters did, indeed knowing their fates, I found myself writing less and less each day, to linger longer among these people, because I finally knew them so well by now, after so many months, even though none of them existed, even though the world they inhabited did not exist, was not even as substantial as a transparent bubble, even though they and their world, still, felt to me hot as a teardrop. That has to be a special type of sorrow, to say goodbye, forever, to people who do not exist. Because as long as a novel is unfinished, you as the writer can think up all sorts of 'what-if' situations the characters can still get into. But once you finish, everybody gets set in stone. The vibrant life you breathed, leaves. Readers don't realize it, but when they crack open a novel, it's already become a museum.

In the midst of the writing, when that world was growing happier each sunrise, I moved forward up to 3,500 words a day. The final day, this past Thursday, I wrote the last 783 words.

Looking back on my life so far, I can see now, from this distance, the events which shaped me, and which constitute me. The time I spent with my grandparents as a child, working in New York City in my late teens, living in California, Mary and me traveling for a quarter-year across America and Canada, getting our cats, rising within the company I worked for, building our garden.

The writing of the four novels I've produced so far: Always Again, Father Figure, Kid, and now As Dead As Me.

After a rest, my next step will be to go back to the beginning, and move forward through the novel again, editing, an enviable task only allowable in fiction. It always delights me to see there are some sentences so good I don't even remember writing them, and of course dismays me to find the tangles here and there where the flower is growing into the ground.

I started writing as a child, by drawing.

One day I took a blank sheet of paper, that horror and hope of all writers, turned it landscape-style, and crudely drew four panels across it. In each panel I created, with my slow pencil, fingers gripped at the whittled bottom, just above the dark lead, so that the top of the pencil waggled, stick figures interacting with each other, in imitation of comic strips, letting dialog balloons sprout from their heads. The stories were simple.

My cousin Janet, older by a year or so, which back then, around age eight, is almost as wide as a parent-child gap, became intrigued by my wavy-sided strips, and started drawing her own. At one point, I suggested we have a contest with each other, to see who could draw the most comic strips over the course of a Summer.

I won. Part of my triumph may have been that I had more ideas than she did, but most of it was that I was simply more obsessed than she with drawing stories.

What did I draw that idyllic childhood Summer of green sea water and rows of rhubarb plants, and old Christmas cards from the nineteen-thirties found inside books in my grandparents' attic? Mostly campers in a brown forest threatened by an upright bear (I was good at drawing tents), and flying saucers death-raying our beloved planet, the sideways-oval helmets of our defending soldiers no match for the saucers' emissions of squiggly No. 2 pencil lines.

None of this nonsense made me a writer, of course. Around August, I was running out of scenarios. Suspecting Janet and I were about even in our production (we never discussed how many separate panel-stories each of us had created in our contest, but her pile seemed as high as mine), I put a fresh sheet of paper down on my desk, turned it landscape, and drew my first square. What will I fill it with?

In the middle of the panel I drew a stick figure of a little boy lying on his stomach, head lifted.

In the right space of the panel I drew the boy's object of attention. A square-boxed TV set.

I drew a speech bubble over the boy's empty oval head, but sitting back, I couldn't think of anything to fill that bubble. To this day, I remember turning my pencil upside-down, like turning my world upside-down, and erasing the bubble, leaving on the white sheet little bits of maroon eraser debris that had to be gently blown away. I became an editor.

Then I didn't do anything for the longest time.

Eight year old boy, sitting in a chair still a little too big for him, elbows on the desk in his bedroom, looking down at the sheet of paper his elbows bracket: boy on his stomach, TV.

Do you know what I did then?

Something I wasn't supposed to do.

For whatever crazy reason, I drew a speech balloon for the TV instead, but coming out of the back of the TV, which didn't make sense.

I drew that balloon so wide, it became tumorous, invading, indeed filling, the white virginity of the next panel.

Instead of stocking the balloon with words, across the interior top I added long, triangular stalactites, as pointed as upside-down witches' hats.

Across the floor of the balloon, I added tall, pointy stalagmites.

What had I done? I had leaned my imagination against the right wall of one panel until it collapsed across the next panel. I had created an exciting new idea for me. Behind a TV set, beyond my parents' living room, is a cavern that leads down and up, chunky with gems, wherever I want to go.

That's when I discovered words are holes.

That's when I discovered I was a writer.