lately

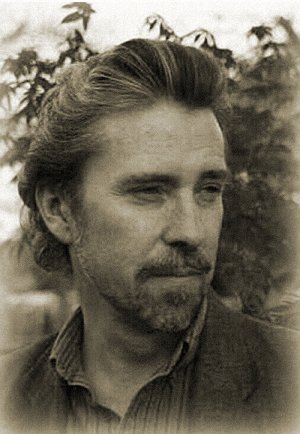

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2002 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2002.

"i want to make my movie"

This Lately continues the story of my wife Mary's recovery from a recent stroke. The first part is located here.

As I said last week, by Sunday, April 21, things looked better. Mary had been rushed to the hospital by ambulance the previous Wednesday, April 17, completely paralyzed on her right side and unable to talk. Although she was still in the Critical Care Unit of Medical City Dallas, she was expected later today to be moved to the sixth floor, the hospital's neurology center. In addition, Joe, Mary's dad, was flying down from Milwaukee today to stay at our home for a few weeks, to help out. I knew the sight of her dad would help Mary tremendously, since they're so close. His being here would also help me. By this point, I had slept very little since Wednesday, and eaten virtually nothing. My life consisted of sitting by Mary's bed in the CCU, holding her hand and talking quietly to her, encouraging her; wandering around the immense, never-ending corridors of the first floor of the hospital when I had to leave for a half hour or so, so the nursing staff could perform different tests; and driving the near-deserted multi-lanes of the highways late at night to get back to our home, or early in the morning, to get back to Mary.

One of the first nights of Mary's stay in the CCU, while they were examining her, I found, in my wanderings outside in the dark, a fountain, set in the center of the hospital complex, benches arranged around its large, stone circle. When I had to leave her side for a while I'd go there, sitting by myself in darkness, smoking my first cigarette in hours, which made my head tingle, usually at such a late hour no one else was around, or just some orderlies on break. I'd stare at the bubbling rise of the fountain, the way each white spurt fell back into the pool, thinking how much Mary would enjoy seeing this, praying she'd get better. One time while I was down there, the fountain suddenly stopped, just like that. I rushed back upstairs, but she was fine.

It seemed by this Sunday that the drug they gave Mary as soon as the ambulance got her to the emergency room, TPA, had in fact worked after all (her emergency room neurologist initially thought it hadn't). Mary had a clot in her brain the size of an egg (as one of the doctors in CCU told me, and another confirmed). TPA is a powerful blood-thinner. It reduces the size of the clot quickly, to reduce damage in the brain. One of the side effects of TPA, since it is a blood-thinner, is that it leaves large bruises on the extremities. In fact, when I first saw Mary in the emergency room that Wednesday, both her forearms were heavily bruised, and the back of one of her hands was almost black. Throughout those early days, while she tried to talk to me but couldn't, she'd rediscover these horrible bruises on her forearms, in distress, and I'd explain to her again how they got there, and that they would go away.

But now, today, Sunday, she was able to walk fairly easily around the CCU corridors with me or a physical therapist by her side. While we waited for Joe to arrive, another therapist came into Mary's cubicle with a small tray. On the tray was a glass of soda, a straw, a tablespoon of jello on a paper plate, and a half cup's worth of porridge.

"Mary, we want to see how you do trying to drink and eat, okay?"

Mary lifted her head off her pillow, looking at me, nodded at the nurse.

"Let's try the jello first, okay?" The therapist picked up a small wobble of the jello on a plastic spoon, and holding her palm under the spoon, brought the jello up to Mary's mouth. "Can you eat this?"

After a moment Mary understood what she was supposed to do, and put her lips over the spoon, pulling in the jello, looking up at the therapist.

"Is that good? Can you swallow it?"

I tensed, watching Mary's throat as she swallowed.

"Good! Do you want to try to put the next spoonful in your mouth yourself?"

She did, and did great. She was also able to drink from a straw, hold the soda glass and drink directly from it, though it seemed heavy in her grasp, and feed herself the porridge.

"That's great, Mary! We'll remove the IV lines from her, and start giving her solid food. You did great, Mary!"

(While Mary was in the hospital, I came into contact with dozens of doctors, nurses, head nurses and therapists, which was really the first time I had ever dealt with the bureaucracy of a large, metropolitan hospital. We all hear horror stories about how these places are run, and I have no doubt there is unneeded horror in the hospitals, but even though I occasionally ran into someone who was overly hidebound to the rules, too zealous in protecting their authority, or in one or two cases, completely indifferent to everything, the majority of the staff in my own experience were caring, helpful people, especially, even above the doctors and nurses, the therapists.)

In the early afternoon of that Sunday, I turned around from Mary's bed at one point to see her dad, Joe, walking towards us.

Joe had been picked up at the airport by Joel, the Senior Vice President where Mary works. Throughout this period, Joel helped greatly, picking me up at home that first day to get me to the emergency room, getting Joe from the airport, helping out in many other ways. Gayle, Mary's assistant, helped tremendously too, as did Susie, Mary's friend, who took Joe the next day to a car rental agency, so he could have his own car during his stay. All her co-workers and friends really rallied round for her, helping in every way they could, often at considerable inconvenience to themselves. Their efforts made a big difference. Having gone through this now, I can't emphasize enough how important it is, early in a crisis like this, to get as much support as possible from others.

I had mentioned to Mary on Friday, after I spoke to him on the phone, that her dad was flying down to see her, and rementioned it once or twice a day since, but I think at that early point in her recovery the information didn't really stay in her mind, so that each time I brought it up again, as something she had to look forward to, she reacted as if it were the first time I had told her. Each time, her initial reaction would be that as much as she wanted to see her dad, she didn't want him to have to fly all the way down here. But once I assured her he was fine about that, she'd get excited.

Seeing her dad now, in the CCU, Mary got a huge grin on her face. The tubes and wires and catheter had been removed by this point, so they were able to hug, after which Joe and I hugged. The three of us sat in Mary's cubicle, Joe and me talking to Mary, Mary laughing and nodding, then Mary got to show Joe how she was able to walk again.

Joe, bless him, brought with him color print-outs he had made of some pages from Mary's website that she had added just the weekend before her stroke. As she looked at them, Joe pointing out the details of the pages, things Mary would likely remember in composing them, some recognition came to her. She looked at her dad, smiled. "Yeah."

Later that Sunday, Mary was transferred up to the sixth floor. Joe and I carried her belongings while one of the nurses pushed her wheelchair (inside the hospital, and I suppose this is true of any hospital, all patient transport is by wheelchair, whether it's needed or not).

Once I found out, the previous day, Saturday, that Mary was being moved to the sixth floor, I started asking everyone involved with her case-- doctors, nurses, therapists-- if it would be at all possible for her to have a private room on the sixth floor. I wanted this because I knew, for one thing, that that would be Mary's preference, but also because if she did have a private room, it meant I could sleep over. Just before the transfer, one of the staff told me quietly that Mary had been bumped to the top of the list, and would indeed get her own room.

Once we were on the sixth floor, Joe and I met the staff up there, and Mary walked around her room. One of the first things she did was pull the drapes of the window open. The window looked down, in one of those coincidences, on the plaza and fountain I'd go to those first nights to smoke and stare at the water. Things were so much different now!

Since Mary was able to eat and drink, she was put on rotation for hospital food, which she was enthusiastic about when the tray was first set down in front of her-- food! After so many days!-- but which she wound up only eating a few forkfuls. I tried it myself. Pretty bland. I urged her to eat anyway, if not for enjoyment, then at least to build up her strength. Her right hand traveled over all the packages on her tray, opening up containers of apple juice, a piece of chocolate cake, hot soup, crackers, and she duly took a bite, or at least smelled, all of them, but none of it appealed to her. I myself went downstairs at one point to the food mezzanine. There were three stands, for Chinese food, for barbecue food, which advertised itself as one of George W. Bush's favorite barbeque restaurants, and a place called Fruitella, or something like that, which I took to be basically a fruit stand. By this point, I had lost about twenty pounds since the Wednesday of Mary's stroke, but hadn't really been hungry. Now that Mary was out of CCU though, and Joe was here, I was feeling much better, and thought I'd try to eat something. I had tried the Chinese restaurant the other day, ordering sweet and sour shrimp, which I normally like, but hadn't been able to eat any. And I didn't really feel like barbecue. I made my way over to the Fruitella stand, reading the menu board, and saw they made sandwiches. I got what they called a club sandwich, which was served on untoasted bread with ham, turkey, lettuce and cheese, brought it to the clearing inside the hospital of nearly empty tables where people could eat what they ordered, and surprised myself by wolfing it down.

Later that evening, Joe and I went down to the food court and bought some sandwiches from Fruitella. As we finished eating them, I noticed Jim and Peggy, our next door neighbors, standing nearby. The Thursday after Mary's stroke, when I pulled our car into our driveway to quickly feed the cats, grab some sleep, and return, Jim and Peggy had, at the same time, pulled into their own driveway. They're great neighbors. We've never been inside their house, but over the ten years we've lived next to them, we've had hundreds of driveway conversations. I walked over now, wanting to let them know about Mary.

Jim grinned at me. "We thought we'd lost our neighbors!" Our lawn hadn't been mowed. It was starting to get seed heads.

I looked at them both. Jim changed his face. "Is everything all right?"

I told them about Mary's stroke. We talked for a while, out there in the driveway. I asked them both to pray for her, and started to cry, but then stopped.

Now here they were at the hospital, to visit Mary. Jim himself suffered a stroke a year or so earlier, though nowhere near as severe.

The four of us rode up in the elevator together. I went into Mary's room first, to let her know Jim and Peggy were here. Both hugged her in her bed. Jim talked to Mary for quite a while, in a deliberately slow voice, telling her about his own experience with a stroke, and how when he was now occasionally confused about how to pronounce a word, he'd find a similar word to say instead. (The next day, when I went home to change clothes, our lawn had been mowed, by Jim).

I stayed over in the room that night. The room came with a chair that folded out into three cushions on the floor. I changed into my pajamas in the room's bathroom, flapping my arms up into the air as I emerged to show Mary I was here for the night. She looked at my hair, made a comical face (I used to always simply wash my hair each morning and then blow dry it however it naturally went. About five years ago, Mary decided to start spraying the front of my hair with a hair spray, to at least keep the locks from flopping over my forehead. Eventually, this morning bathroom practice evolved to where, after I dried my hair, she'd travel around my head with the hair sprayer, spraying me like I was a huge bug, getting my hair in shape. She took a great deal of care in doing this, which was typical of everything she did, so that I'd leave our home actually looking kind of suave. Left to my own, I had tried to duplicate her results, but my hair looked flat and spiky after I sprayed it. Like a lawyer operating out of a glass-doored office.)

I had trouble getting the chair to transform into a bed, to the point where I eventually went out into the hallway and asked a nurse for assistance. She, reassuring to me, also had a problem with the mechanics, but eventually figured it out. Although this arrangement was far from how we'd sleep at home, it was far better than me leaving at some point each evening. I bent over Mary's hospital bed to kiss her goodnight after a USA Network movie ended with its long list of credits, turned off the light, and got down on the three cushions, pulling the white blanket up to my shoulders. I woke up, confused, to bright lights as a nurse came in, an hour or so later, to check Mary's blood pressure.

My shower the next morning was limited to brushing my teeth. I did get Mary in the shower though, stripping off my shirt, hovering outside the opened curtain while she washed herself.

In the days that followed, different therapists came in to assess Mary's condition. We'd walk to a workplace on the neurology floor, where a therapist would ask Mary to get up on a slanted slope and write the name for the current month (April) on a blackboard. She did it. "What month is your birthday?" The therapist looked at me. I mouthed, October. Mary hesitated, picked up the magic marker again, wrote April. "What month is your birthday, Mary?" Mary pointed at the word she had written.

Another test was to have Mary stand on an unstable surface, in this case a large rectangular piece of foam, and try to catch a big, bright ball the therapist would deliberately toss too far to her left, right, overhand, underhand. All these tests were designed to test Mary's ability to balance her body. She passed them all.

When each day's sessions were over, Mary and I would return to her room, to relax. Mary was starting to talk more now, making a little more sense, though most of what she said was still nonsense. Over and over again, she would carefully, painfully enunciate that, "I want to make my movie." That phrase would come up over and over again throughout each day. We'd be watching TV, and she'd reach out and hold my upper arm. "Later. Later?" Sweet face looming closer, lips being so deliberate in getting out the phrase. "I…want…to make…my movie." Then she'd grin at me. I had no idea what she meant. At first, I took her literally, then I realized, over time, that "make my movie" meant something good, but probably had nothing to do with movies. Stroke victims often substitute inappropriate words when they can't find the right word. Similarly, later, she often used the word "sammies", for just about any noun she couldn't conceptualize.

Her sessions on the sixth floor also included physical therapy, where she'd go to a room with a group of people in wheelchairs and perform a hour's worth of arm and leg exercises. During her first session, on Monday, the neurologist who was so dire before he left for his conference out of state watched her, shaking his head. "This is a miracle. I never thought she'd get this better this fast."

While she was on the sixth floor, I'd walk her around the floor two or three times a day, for exercise, and as part of my campaign to show the nursing staff she was physically ready to go home. Because I realized early on that what was contingent on Mary's being discharged was not a recovery of her cognitive and speech faculties, which would take months, but a return of her ability to stand upright without assistance, and walk stairs. On one of these perambulations, we walked all the way out to the front elevators, where there were a bank of windows looking out over the city, and Mary, walking over to the windows, looking out, saw, with a great deal of interest, a familiar Dallas skyscraper. "Oh!" In that moment, I realized she had finally placed, after so many days, where she was.

After a few days on the sixth floor, Mary was transferred down to the fifth floor, which was Rehabilitation. I sat on the side of her hospital bed, using my right hand, lifting it higher and higher, letting her know that each transfer was an important advance in getting discharged. "You started in the emergency room, then CCU, then the sixth floor, and now you're here, on the fifth floor. After this floor, you'll be discharged and can come home!"

There were no private rooms on the fifth floor, which meant I couldn't sleep over anymore. But Mary was definitely getting better. Over and over throughout the day, I kept repeating to her, "You're getting better and better, and stronger and stronger". Flowers weren't allowed in the CCU, but once Mary moved to the sixth floor flower arrangements started floating in from all over, so many arrangements we couldn't fit them all on the table surfaces, and had to put a lot of them on the floor. Joe and I carried the flower arrangements behind Mary's wheelchair as we all trooped to the elevator taking her down to the fifth floor.

On this floor, there were no diet restrictions. Part of my concern was that Mary wasn't eating very much, so I went down to the food court, got a menu from the Chinese restaurant, and brought it up for her to choose what she wanted for dinner that night. It gave me a great deal of encouragement that she looked at the menu, all these choices, and immediately selected Cashew Chicken, something she would normally order, which suggested she had some reading comprehension. I went down in the incredibly slow elevator, brought Cashew Chicken up for her. She devoured it, eating almost half the portion. We ate it watching a local broadcast of Friends, a show we had never bothered to watch before, but now liked, followed by The Simpsons.

Mary was doing so well that that Friday, April 26, they decided to release her. Joe and I showed up early, packing her little suitcase, deciding what flower arrangements we'd keep, which we'd leave behind.

In order for Mary to leave, she'd have to be revisited by her emergency room neurologist. That was supposed to happen at eleven a.m., but the time stretched. He had emergency calls, he was coming, he was delayed. Joe, Mary and I sat around the room, watching TV we would never otherwise watch, waiting for him to show up. Eleven o'clock turned to twelve, to one, to two. He finally came in, apologizing, and gave us a quick talk about the medication Mary would need to take, then left. We waited some more for a nurse to bring us the written prescriptions.

And then, another nurse came in, with a wheelchair. It was over. She could go home.

I went to get the car, while Joe accompanied Mary, seated in her wheelchair, down the elevator to the rush and crowds of the main lobby. I recognized some of the faces in that lobby as I myself hurried across it to the parking lot. I'd seen them over the days talking on cell phones, greeting visitors, sitting by themselves in the rush, just as I had. The hospital was its own little city. What distinguished it were its citizens, all of whom, temporary though they were, shared a thousand different worries which nonetheless held the same core worry. As a consequence, we were all of us more polite to each other than other cities' citizens, more likely to enter into brief conversations with each other, to smile encouragingly at each other. It was the only aspect of the hospital I would miss.

Mary grinned from ear to ear all the way on the long drive home. She stooped over in the kitchen to pet the cats' heads. "Hi! Hi! Hi!" Upstairs, she giggled when she saw the sheets I had used to make Joe's bed that past Sunday night. I hadn't noticed, and I'm sure Joe hadn't either, but they were Christmas sheets.

Downstairs, in the breakfast nook, I pulled up the miniblinds on the picture window overlooking our garden. Her head reared back, stunned. The morning of the day she drove to work, and had her stroke, the trees were bare, the ground nearly devoid of color. Now, in just the nine days of her stay, because of all the rain, time's passage, the persistence of rebirth, and who will ever know what else, the garden was lush, crowded with colors.

We went outside, careful as always not to let out the cats. The three of us walked down a path, Mary in front, jaw dropped, staring all around her, going forward slowly into the garden, back into our peaceful world, into its intense greenness.

More next week.

Please continue to keep Mary in your thoughts. To see some pictures of her, go here. To visit her website, please go here.