lately

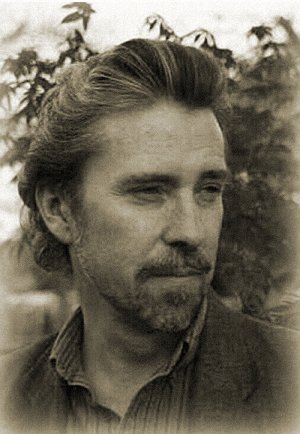

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2002 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2002.

fun with our bodies

One of the exercises we do on our new Body-Solid home gym, which we purchased after Mary's stroke, while seated on it, is to curl the tops of our feet behind a black foam roller below the seat, then lift that roller up, against the resistance of weights, to strengthen the front muscles of our thighs.

Whenever Mary finishes this exercise, she slips her feet free from the rollers, giggling as her shins rise on their own until they're horizontal to her knees.

Her shins rising is an involuntary muscle reaction. If you place resistance against a muscle, so it has to strain to move in a certain direction, once you remove that resistance, the muscle will continue to move in the same direction.

When I was a kid, pre-pubescent, that was one of the favorite activities my friends and I would do with our bodies.

We'd stand with our right side next to a wall, then press our downwards-extended right arm against the wall, pushing the balled back of our hand against the wall as hard as we could, as if trying to push the wall away. After about a minute of intense effort, you'd walk sideways away from the wall, relax, and laugh as your right arm magically lifted on its own until it was at least shoulder high, or sometimes, depending on the effort you had expended, over your head. If you faced the wall instead of standing rightside to it while pushing with your right knuckles, stepping away, you'd give an involuntary Heil Hitler salute.

The lesson we learned, of course, was that there was a joy in losing control over your body. The joy was rediscovered years later when everyone started using drugs. I truly think the attraction of drugs, to a large degree, is not self-discovery, or religious insight, but the relief of being allowed to be stupid. Instead of worrying about how you're going to support yourself after college, all you have to fret about is how to stand up out of a chair, or which knob controls which burner. It's a lot of fun.

People who eschewed drugs often used, as a substitute, to get the same effect, parlor games.

A parlor game back then, at least in my family's circle, was to have a woman stand with her back against the wall, bend over, ass still against the wall, and pick up a straight-backed chair that had been placed sideways in front of her. She could do it every time. A man would then be asked to do the same thing, preferably the strongest guy in the room, and he'd topple forward at each attempt, since his center of gravity was different. Boy, would he look stupid, awkwardly toppling forward the fourth or fifth bend-over before he'd finally give up, grinning red-faced, happy, still the center of attention, this time for his limitations.

My favorite parlor game of all time is what I call the 'ten' game. I've played it for over thirty years. It's a mind game rather than a body game.

Feel free to play it with someone you know who could benefit from feeling stupid for a little while.

It's very simple.

Tell someone you're going to brainwash them. You're going to have them say something, and once they finish saying it, you're going to ask them a simple question, the answer to which they know, and they're going to give you the wrong answer.

The typical response you'll get at this point is skepticism (You're going to try to trick me? Okay, give it your best shot), which makes the end result all the sweeter.

Tell him or her to say the word "ten" out loud ten times fast.

Tentententententententententen.

Then ask them, "What is an aluminum can made out of?"

Their answer will be, "Tin."

Ask them again.

"Tin!"

(They think they've eluded your trick, because they think you made them say "ten" so that they'd say "ten" instead of "tin". They don't understand the ten times repetition of "ten" was a distraction so that they wouldn't comprehend the significance of "aluminum can".)

You'll usually be able to ask them the same question about a half dozen times, getting the same wrong answer of "Tin".

Often, you can even slow your question down, even emphasize the word "aluminum", and they'll still give you the same stupid wrong answer.

After you've befuddled them with the ten trick, you can rebefuddle them by doing the same trick all over again, only this time substituting "step" for "ten", which they must say ten times fast, then asking them, "What do you do when you come to a green light?"

They'll answer, "Stop."

Another mind game is to fold over a piece of paper about four inches high and eight inches long, so you have a long tent two inches high and eight inches long. On one of its sides, divide the side into four equal squares with vertical lines. In the first square write 1, in the second 2, in the third 3, in the fourth, 4. Keep this tent hidden.

While the person you want to play the game with is watching, cup your hand around a piece of paper, write on it, "You chose 3", then fold the paper in half so it can't be read, or seal it in an envelope for a dramatic effect, and pass it over to them, telling them not to look at it yet.

Take out the long tent with the four numbers, not showing the numbered side to them yet, ask them to quickly choose a number, then place the tent, numbered side to them, on the tabletop.

They'll almost always choose 3, because the way our minds work, we look first to the right of center.

Once they choose 3, tell them to unfold the paper you handed them, or open the envelope. They'll usually keep flipping the piece of paper with "You chose 3" on it over and over, trying to figure out how you knew what number they would choose.

There can be something wonderful about confusion.

I've noticed my own exercises on our home gym have started to give me the fabled washboard stomach. It's not large enough yet to wash anything as big as a grass-stained football jersey, but at this point it could probably handle a little girl's communion dress.

Our cat Rudo's appetite has decreased since he's started receiving treatment for his kidney disease. He's lost some weight, and will only eat dry food. Chirper, his unwanted sidekick, who imitates Rudo relentlessly, even to lying on the carpet the same way Rudo does, has also decided, taking his cue from Rudo, he doesn't want to eat wet food anymore. I can understand Rudo's turning his nose up at the wet food, given the ordeal he's going through, but not Chirper's.

Tonight when I put their wet food down, Rudo sniffed his, limped away. Chirper, who's perfectly healthy, but eyes sliding sideways, took an imitative sniff and did the same thing.

I airlifted him back in front of his bowl. "Eat your goddam food. There are cats starving in India."

This past Wednesday, I went back to the hospital where Mary was ambulanced following her stroke, to get copies of her medical records. I've found a neurologist for her, and wanted to turn the records over to him, so he could examine them to see if he could determine the cause of her stroke, and also so he'd be familiar with her case.

It was the first time I had been back to the hospital since April 26, the day Mary was discharged.

The huge mezzanine was crowded as ever, lots of worried people on cell phones, family members with flowers and balloons greeting each other in the commotion. As I walked to the Records room, I passed by the Fruletti stand where I'd buy sandwiches each day during Mary's stay, and heading down an interior hallway, noticed, through glass sidedoors, the fountain I used to go to those first rainy nights to pray for her recovery.

I sat down at our breakfast nook kitchen, an hour to go before I had to leave to pick Mary up from her speech rehabilitation that afternoon, and quietly went through the medical records.

It was all there, the hastily scribbled emergency room notes indicating different tests to be performed; the columned critical care unit forms with check marks recording her physical and mental capabilities each day, numbers inked-in tracking her blood pressure and pulse rate; the formal, typed reports summarizing the different doctors' findings.

Mary's condition, aphasia, which is a result of her stroke, causes her to have difficulty with the concept of speech. The best way I can describe the problem she's gradually overcoming is to think of the last time you tried, for example, to recall the name of an actor, and the name stayed on the tip of your tongue, tantalizingly close, but unrecallable. With aphasia, every word you try to say is a "tip of the tongue" word.

But she is making remarkable progress, and in fact can create some sentences now, often startling me after all these weeks of watching her lips struggle to shape a single word.

She's still the same Mary, but a different Mary as well. The world is fresher to her, filled with fairy tales. When we go to the park, she waves to the ducks, and twists her head around, as we leave, to call "Goodbye" to them. When she smells something, a flower or loaf of bread, in a sensory confusion, as she sniffs, she also kisses the object.

As lovers do, Mary and I have often wished we could have known each other as children. I think in many ways, these past few weeks, I've been privileged to be in the presence of, for a blessedly short time, little Molly.

Every once in a while I get asked what I've been reading, so here's an update.

I usually arrive at Mary's rehab center a half hour early, to make sure she doesn't have to wait for me. During that half hour, I leave the engine on for the air-conditioning, and reach in the back seat to pull out my current book.

I started, in the first weeks of Mary's therapy, with a reread of Nicholas Baker's The Size of Thoughts, because it was familiar and therefore reassuring to me, a collection of his essays on commonplace objects such as fingernail clippers, for which he first became famous; as well as the ingenious Books As Furniture, in which, with a magnifying glass, he determines the titles of the books left lying around the photo spreads of different popular catalogs, such as Crate & Barrel, and investigates them; the book finishing with the thoroughly enjoyable hundred-plus page essay Lumber, which traces the use of that word (especially its British application) through centuries of literature. Baker likes to show off, and he's at his puffed-up best in this book, although I disagree with his decree that "A bee must never be allowed to shoulder", in his review of Alan Hollinghurst's The Folding Star, in reference to the opening of The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which Wilde depicts bees "shouldering their way through the long unmown grass", which I always thought was a great image, better than any Baker has yet to produce.

After I finished The Size of Thoughts I took up Maitland McDonagh's Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds, a study of the films of the Italian writer/director Dario Argento, whose movies I've always admired. It's a good analysis of Argento's themes.

The book I'm midway through now is Brian Boyd's Nabokov's Ada, The Place of Consciousness, which discusses many of the hidden, inter-connected clues in Ada, Nabokov's most difficult novel, and also puts the concerns of Ada into the larger context of Nabokov's work in general (the major aspect of Nabokov's works, metaphysics, was generally undiscerned, despite hundreds of books and articles on Nabokov by Nabokov scholars, until his widow, Vera, pointed to the theme shortly before her death. Boyd's book helps show the hollows and tension lines of that theme all the way back to the beginning of Nabokov's writing career.) If you think Nabokov was a great writer, as I do, you'll find the book fascinating.

Once I get through Boyd's book, my next read is already at hand: John Bayley's Elegy for Iris, a memoir by British novelist Iris Murdoch's husband, John Bayley, of his life with Murdoch, including the sad end of her life, when she fell victim to Alzheimer's disease, "the cruelest of diseases", the same affliction that felled my mother.

In between all these books I also read, at 3:30 one morning, I keep odd hours now, Kevin Fanning's Twelve Times Lost, a self-published collection of eleven of his stories, all of them interconnected, all dealing with a sense of disorientation, either highway-wise or within one's own family. I've always admired Kevin's style and concerns in his fiction, and the book is a good introduction to him if you don't already know him. The saddle-stitched book is available here, and only costs a dollar (and that dollar includes postage). I heartily recommend it.

The editors of the annual anthology The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror, put out by St. Martin's Press, have awarded my story Visibility an Honorable Mention. I'm very grateful. The story originally appeared in Trevor Denyer's U.K. magazine ROADWORKS. You may read the complete text of Visibility here.