lately

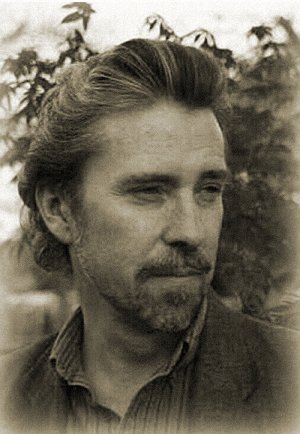

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2017 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to lately 2017.

my seven cousins

What I loved most about the early Bond movies was the music, specifically the "James Bond Theme" that plays at the beginning of each film, that urgent, repetitive guitar pulse while we get a view from the inside rear of a spiraled gun barrel, see a man in our sights. And then shoot him.

To a teenager sitting with his pals in the Greenwich Playhouse on a Saturday morning, Dr. No signaled a new attitude. At a time when, like any young person, I was looking for ways to transform from a child to an adult, here was a role model whose life was an adventure. "Bond. James Bond." I wanted the steadiness of those blue eyes, the curly black hairs over the carpal bones of those wrists.

I bought all the Ian Fleming novels in paperback as soon as each came out. Absolutely devoured them, turning page after page, so entranced, so happy. About this time, Life Magazine asked President Kennedy what his ten favorite books were, and along with a number of respectable, time-honored classics, he listed, at number ten, From Russia with Love. Pundits theorized he put a Bond novel on his list to show his affinity for "the common man", but I always figured that was just the young teenager in him admitting they were exciting.

On the back cover of each Bond paperback was the same author photograph of Fleming holding an upwards-pointing gun in front of his profile, and in fact during World War II he was a member of the OSS. Fleming was known as a heavy drinker, heavy smoker. He said once, "I shall not waste my life trying to prolong it." Which I really liked. After a heart attack in 1963, he suffered another, fatal heart attack in 1964, on his son Casper's twelfth birthday. (Eleven years later, Casper committed suicide with a drug overdose.)

Ian Fleming

May 28, 1908 - August 12, 1964

56 years old

"Might I be permitted to smoke?"

As a child I was first introduced to horror films watching the classic black and white Universal classics on TV. Dracula had some good moments, The Wolfman as well, The Mummy perhaps less so, but nothing resonated as much with me, and I think with a lot of children, as Karloff's portrayal of Frankenstein's monster. His mostly wordless performance (the heart-rending "Friend"), black-sleeved arms waving stiffly from his sides, flat-topped head swinging uncomprehendingly left and right, was one of the few mime performances I've enjoyed. And he really did portray the uncertainty and confusion children feel, trying to fit into an adult world. He was as innocent as a child, but as vindictive as a child as well ("We belong dead").

As I learned more about Boris Karloff, the actor who portrayed the Frankenstein monster, I was struck by Karloff's gentleness, his good manners. Never do I feel better than when I'm being polite. If I remember correctly, it was in an issue of Famous Monsters of Filmland where Forest J. Ackerman quotes Karloff saying, at the end of a lunch with ladies, "Might I be permitted to smoke?" I was taken with that eloquence, the way in which he had phrased his inquiry. Not, "May I smoke?" but the far more gracious, "Might I be permitted to smoke?" At one point in my New England childhood I sent him a request for an autographed picture, feeling so sophisticated putting a stamp on a letter that was going to travel all the way to Hollywood, California, and a few weeks later, received an autographed black and white glossy. I was thrilled! It became one of my few treasures, although now, so many decades later, I have no idea what happened to it.

Boris Karloff

November 23, 1887 - February 2, 1969

81 years old

There was a discount store chain, local to the East Coast, K-Mart, when I was a teenager. My family would drive out there once a week, and while my parents looked around for cheap bedsheets or bulk toilet paper, I'd make a beeline down the escalator to the lower floor, where on the left would be the record department, wearing the same dark green jacket I wore everywhere during my early teen years, as if it were a protective cloak when out by myself among a crowd of strangers. Albums--The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Jefferson Airplane--were only $2.76. Even then, I realized what a bargain that was.

And one day, flipping the tops of the square-shaped albums in the New Arrivals bin, I came across a new album, The Doors. Never heard of them. Which was good. I risked my $2.76 plus tax. Got home, went upstairs to my room, shut the door (didn't we all? What teenager leaves their bedroom door open?), put it on my turntable. First side was really interesting. Break on Through, Soul Kitchen, The Crystal Ship, Twentieth Century Fox, Alabama Song, Light My Fire. Rock with a prominent organ sound, which was unusual back then, plus an electric guitar with heavy flamingo influences. Flipped the black LP with its circular grooves over, to side two. Back Door Man, I Looked At You, End of the Night, Take It As It Comes, and the shock, the masterpiece, the thrown-down gauntlet, The End.

I had never heard a song like The End before. No one had. Rock back then sang about love, drugs, politics.

"The killer awoke before dawn, he put his boots on.

He took a face from the ancient gallery

And he walked on down the hall.

He went into the room where his sister lived, and then he.

Paid a visit to his brother, and then he.

He walked on down the hall, and

he came to a door, and he looked inside.

Father? Yes, son? I want to kill you.

Mother? I want to fuck you."

This wasn't I Want to Hold Your Hand.

There was an other-worldly atmosphere to the album. It was talking about other planes of existence, desperation, self-destruction. During one show in Miami, Morrison while on stage pulled out his cock and showed it to the auditorium. I applaud him for that. Drunk and high as he could often be, he was trying to break on through, much like decades later, Tig Notaro, performing topless, showed the audience during her stand-up routine the scars from her recent double mastectomy for breast cancer.

I had a gray VW bug back then, little bit bigger than a tricycle, engine power of a lawnmower, I remember driving down Greenwich Avenue, windows rolled down, it was Summer, block after block hearing multitudes of songs blaring from the sidewalks on either side, from pedestrians' transistors (and I just realized that at some point this sentence will need to be annotated). That was the Sixties. Music everywhere. And all different types of music. Rock, soul, novelty songs, jazz, big band, country. Almost every radio station would play this wonderful mix of genres, and it was really good.

And while I was driving down Greenwich Avenue that afternoon, I heard, from the sidewalk on the left, Light My Fire. This was several months after I bought the Doors album, and the first time I had ever heard a song from it in public. A bit afterwards, Light My Fire rising up the charts, Ed Sullivan had them on his Sunday variety hour. Sullivan featured a different rock band each week to boost his ratings. An appearance on Ed Sullivan would make a rock group, leading to a huge increase in record sales. One of the times he had the Stones on his show, he made them change the lyrics of Let's Spend the Night Together to Let's Spend Some Time Together, and Mick had meekly gone along with the censorship. Sullivan told The Doors that to appear on his show they'd need to change a lyric on Light My Fire from "Girl, we couldn't get much higher", to "Girl, we couldn't get much better".

The Ed Sullivan Show was broadcast live. When it came time for The Doors to perform Light My Fire, Morrison defiantly enunciated into the camera, "Girl, we couldn't get much higher." The Doors had been scheduled to be booked six more times on the Sullivan show, but after Morrison's refusal to be censored, they were banned from the most powerful marketing tool in America. And I admire him for that. Don't ever let anyone tell you what to say, or what to think. It's not their mouth; it's not their mind.

Jim Morrison

December 8, 1943 - July 3, 1971

27 years old

I finally got around to reading Lolita when I was about fourteen. I'd see it occasionally on the carousel paperback racks at the different pharmacies and stationery stores I'd visit, but for some reason thought it was a novel about growing up in Russia, which didn't really interest me at the time. When I finally did pull the paperback down and head towards the bespectacled man standing behind the cash register at the glass counter by the front door, scooping quarters out of my jeans, and all those quarters were made of solid silver back then, beautiful art objects we'd soon lose forever, I was looking forward to finally giving this acclaimed novel a try.

Well. Got home, had dinner, went up to my room, lay in my bed fully clothed, on my back, held the paperback up over my face, the way I would sometimes read back then, flipping to the first page of text, bending the left even-numbered side of the paperback behind its spine, like a thin elbow behind a back, and after I got through the Forward by John Ray Jr., and started the novel proper, I was in love. I had never before read anyone who had that absolute confidence in his writing. "(picnic, lightning.)"

Nabokov constructed perfect sentences, dripping like delicious sandwiches. Embarrassing as this is to admit, I always hoped, as a young writer, he would at some point read something I had written, and give his appraisal of it. But of course he never did. He and Vera moved to Montreux, Switzerland where they spent the rest of their lives. Nabokov, out on a hike one day, had a heart attack on a slope near where a tram ran. The passengers on the tram, seeing him gesticulating for help, thought he was clowning around, and ignored his pleas. Perfect for an incident in a Nabokov novel, but not so good for Nabokov himself, the man, the husband, the father.

Vladimir Nabokov

April 4, 1899 - July 2, 1977

78 years old

Mary and I were living in Maine, moved there from California, when Paul Prudhomme's first cookbook, Louisiana Cooking, came out. We read a lot about it, in the New York Times and elsewhere, and bought a copy.

It was a revelation. Prudhomme had a completely different approach to cooking, based not on ingredients or cooking times, but on carefully transforming ingredients in a hot pan until they all come together in their optimal combination. Throughout his life, he kept exploring different ways to cook food, whether it was tossing aromatics (onion, celery, green bell peppers, garlic) with oil before adding them to a dry skillet (as opposed to the traditional method of heating oil in a skillet, then adding the aromatics); or 'bronzing' meat, which to him meant heating a dry skillet to 350 degrees, which takes about 20 minutes, then placing a seasoned piece of meat in the skillet with absolutely no oil, leaving it in place until you see the heat cook the piece of meat halfway up its side, then flipping it over-- done right, it can produce remarkably succulent, juicy meat.

A good cookbook will maybe produce one or two worthwhile recipes. Which is fine. Prudhomme's cookbook produced over ten excellent recipes. I have never known anyone who was so adept at balancing spices and herbs.

Our wish was to eat a meal he himself had cooked. Never happened. When Mary and I went to New Orleans our first time, in 1982, we walked over to K-Paul's, his restaurant in the French Quarter, but it was festival seating, you're sitting at the same table with a dozen strangers, and Prudhomme himself apparently wasn't in the kitchen during the time we were there. Later, living in Texas, we visited the grand opening of Central Market, only realizing once we entered the crush and confusion of the crowds for those opening days that Prudhomme had been there just the day before, in person, to do a cooking demonstration. A year or two later, Mary got a chance to meet one of his cousins through her work. He told her a lot of the family was mad at Paul, because Prudhomme had taken family recipes and claimed them as his own. Whatever. The best home-cooked meals are Prudhomme dishes.

Paul Prudhomme

July 13, 1940 - October 8, 2015

75 years old

I had read a lot about David Bowie, in Rolling Stone magazine and other publications, before I ever heard one of his songs. And then one night, on the car radio as I drove around the dark backstreets of teenagerland, there it was, unexpected, Space Oddity, guitar notes floating up like gray and white bubbles out of my dashboard's speakers.

I loved his voice. There was something so sincere and naïve, but with raw ambition, in that voice way back then, as he strove to start a career in pop music. Over the years that followed, the decades that floated by, that voice became more and more complex, until it was extraordinarily nuanced. Along with everything else he was, he was also the greatest stylist of our time, blending different UK and American accents in his performances, fluctuating from high to low register with a monk's casual ease, toying with phrasing in a way Frank Sinatra wouldn't dare, 'Fame' from Scary Monsters, when he sings with deliberate awkwardness, stretching one syllable over two notes, "…shout it while they're dancing on thhhheee dance floor".

He was a genius. Our genius. He helped 'usher in an age' where people could be accepting about themselves and absolutely everything about themselves, including sexuality. Back then, Mick Jagger said in an interview that Tom Petty was so good, Jagger would be happy to suck Petty's cock. We were so much more casual and open about our complexities. We understood Walk on the Wild Side.

Bowie created some incredible albums, from Hunky Dory to Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane to Station to Station to Low to Lodger to Scary Monsters, then he kind of lost his way. Let's Dance made him, for the first time, a truly international superstar. BOWIE! And I think that level of fame caused him to choke, to stumble across thhhheee dance floor. Mary and I still listened and danced and sang along to the older albums, joyfully, they remained a part of our lives, but after a while, I think after the ironically-named Don't Let Me Down, we stopped buying his records. I saw a video of him on YouTube where he picked up the morning's newspaper, chose a headline, then created a song on the spot for the reporter interviewing him, kind of arrogant about being able to do that, and it made me sad. He seemed to be saying his songs now didn't come from him, from his soul--they came from his learned technical ability to put words and chords together in a semblance.

And eventually, he went away. Disappeared. Poof. In the early years of the twenty-first century. No new releases, no interviews, no appearances. No one knew what he looked like, for nearly ten years.

And then on the morning of January 8, 2013, I woke up, went upstairs about four in the morning, windows black, turned on my computer, read my overnight emails, went to Facebook, and Hey! Bowie has released a new song, Where Are We Now? And it was absolutely beautiful. The old Bowie, with the nuanced vocal delivery, but with new things to say, finally. And we saw him again! Older, frailer, but honest about not hiding how he had aged. And I so admired that frankness. That was the Bowie I fell in love with, the Bowie millions looked to for inspiration and consolation. More so than any other artist, Bowie got us through our lives.

The rest of The Next Day wasn't as good of course, but no matter. Bowie was back. A while later he released his demo of 'Tis a Pity She Was a Whore, which was brilliant, and then his final album, Blackstar, which I thought was a true leap forward, stunning and affecting, so many great songs, then he died. "Look up here, I'm in Heaven."

David Bowie

January 8, 1947 - January 10, 2016

Age 69

While I was working in Manhattan in the late Sixties I decided one night after punching the time clock to wander over to 42nd street, to see what movies were playing. I didn't feel like taking the train home to Connecticut just yet. It was a weeknight. Back then, brightly lit 42nd street was lined on both sides with movie theatres, marquee canopies hanging halfway out above the sidewalk, some major Hollywood releases, but mostly B movies.

And that night, I spent my money to watch a double bill of Dr. Who and the Daleks, and Night of the Living Dead.

Dr. Who was forgettable. I concentrated on lifting popcorn to my lips. But then Night started, and everyone in that theatre stopped what they were doing, some sooner than others, and stared up at the screen as the story unraveled.

Probably the greatest horror movie of all time. The occasional clumsiness of the acting, the stock music library soundtrack, the plainness of its setting only added to its dread. It was not so much a movie as a nightmare. The line that was finally crossed between the old-fashioned horror movies of the past (Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolfman), and the modern, post-Holocaust films that came after (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Henry, The Hills Have Eyes, I Spit on Your Grave).

By the time it was over, everyone was in shock.

Years later, living in California now, I saw the sequel, Dawn of the Dead, not by my lonesome self, but this time with the love of my life. Mary and I went to a midnight showing in Santa Barbara, I remember us standing in the lobby, waiting to be let in with the rest of the crowd into the theatre proper, and even though the film had just opened, there were already overweight women in the crowd wearing Dawn of the Dead t-shirts. Watching the movie that night was one of the most uncomfortable experiences I've ever had in a movie theater. Just the sheer bloodlust of the audience, people cheering, pumping their fist in the air whenever someone was eaten. When we got back home to our apartment, we just wanted to go to bed.

Romero had true talent. And I think part of honoring him, of respecting him, is to acknowledge that as great and original as some of his films were, the original Dead trilogy, Knightriders, Martin, one or two others, he also made a number of films that weren't at that level, often because of budget, and that must have been so frustrating to him. But he kept plugging away. Through no fault of his own, the original Night of the Living Dead was released without copyright protection, which meant that this career-defining film of his, early in his life, one of the most-cited movies of the post-war period, never earned him the money for which he would be otherwise entitled. That had to do something to him. But his bearded face kept smiling, he kept plugging away.

George Romero

February 2, 1940 - July 16, 2017

Age 77

Ian Fleming taught me to put a sense of adventure in whatever I write. Because like life is an adventure, if you allow it to be, so is art an adventure.

Boris Karloff taught me to separate my art from my life.

Jim Morrison taught me to go deep inside, and not worry about being thought a fool, or being a fool.

Vladimir Nabokov taught me to obsess over every word, because every word a writer puts down is another polaroid of that writer's face.

Paul Prudhomme taught me to care about what I create, to make it as perfect as possible, because what I create is me, it's more me than my hand is me.

David Bowie taught me to laugh at myself, and to always be open to finding new ways to laugh at myself.

George Romero taught me to accept that I will never succeed to the degree that I wish, that there is the ideal, and that what I manage to create? After the struggle and the failure, the art I've produced? Those are the remains.

These are my seven cousins, and now they are all dead.