lately

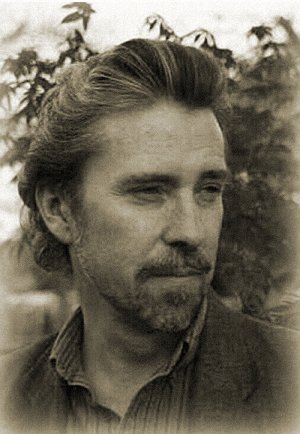

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2001 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2001.

the loneliest sound in the world

There is, in life, something I'll dub the Dentist Appointment Syndrome (DAS).

DAS is living with the knowledge that sometime in the near future (a day, a week, a month), you have to do something you don't really want to do.

For a long time, science in the West, particularly in America, has ignored the similarities between human and animal behavior. If we perceive, for example, an emotion in an animal, whether that be sadness, glee or mischief, we have been taught with a heavy thumb upon our heads that we are anthropomorphizing, projecting our own emotions into a creature without feelings, like shining a flashlight into a clay vase (this prejudice against detecting emotions in animals settles in early, children taking pride in being able to pronounce the word 'anthropomorphizing'). Most of us, more than once, have been told by a dolt that the reason why cats rub their sides against their owner's calf is not due to affection, but to warm themselves, as if we all live in a perpetual Winter. The Japanese, to their credit, have long recognized that animals do, indeed, live complex emotional lives, a concept finally being grasped, these past few years, within the 'one-inch thoughts', to quote Bowie, of scientists.

So if animals do feel emotions, and do use tools, and are so similar to us in so many other ways down the checklist, DAS may in fact be the final bright line separating us from other creatures.

Only humans do something they don't want to do.

No dog would make an appointment to have a colonoscopy. No cat would call another feline over to a corner of the carpet and say, "Your performance this past quarter hasn't been satisfactory. You're fired."

My own upcoming DAS is an appearance in court I have to make next Thursday, August 30.

I was in charge of all legal matters for the company for which I worked. Among other responsibilities, I had to handle all lawsuits brought against us, coordinating our defense, hiring outside attorneys to represent us.

During the time I held this function, for approximately five years, about two dozen lawsuits were filed against my company.

The case I'm testifying in next week is the only lawsuit that has actually gone to trial. All the other lawsuits were settled out of court.

Nearly all civil lawsuits are settled before they ever get to a judge. A civil lawsuit is a dispute between two parties where the nature of the dispute does not involve criminal activity. For example, if someone slips on the washed floor of a fast food restaurant and sues the restaurant, that's a civil case. If someone shoots someone in a fast food restaurant, it's a criminal case.

Civil lawsuits are expensive. In Dallas, where I live, a civil lawsuit takes at least two years to come to trial. That's two years of paying an attorney, at anywhere from $90 to $150 an hour, to review the case, take depositions (sworn statements from individuals with knowledge about the case), respond to discovery (requests for relevant documents) and interrogatories (questions put forth by the other side which must be answered), filing motions, and preparing for trial.

Most companies have a "cut-off cost" when it comes to lawsuits. From experience, they know how much it will cost to defend themselves. If the amount being asked for in a lawsuit is less than the cost of a defense, the company will typically pay the amount they're being sued for, even if they're innocent. Defense attorneys generally know what the cut-off cost is for each major company, and will sue for slightly below that amount. This is especially true of service industries, such as supermarkets and fast food restaurants. They accept, as part of their cost of doing business, this type of legal shakedown.

In the case of the lawsuit in which I'm testifying next week, a municipality is suing the company I worked for, saying, in effect, that my company was negligent in its duties (I don't want to go into a lot of details before my testimony, for obvious reasons. Next week, after the trial is over and the verdict is in, I'll give more information). They're suing for about $100,000. So far, the company has spent about $50,000 defending itself, and the cost of the trial is still ahead of us, as well as the cost of an appeal to state court, if that becomes necessary.

The DAS for me is that I have to drive up to northern Texas, just below the border with Oklahoma, and be cross-examined for a day in public court. Not the worse thing that's ever happened to me, of course, and trivial compared to things some of us have had to do, but still, something unpleasant I'm not looking forward to. Like most DAS, I could simply refuse to do it, since I no longer work for that company now, but I feel an obligation to see this thing through, especially since I'll be the only defense witness. Without my participation, the company will almost certainly lose the case.

An additional DAS for me is that I have to lose some weight in order to testify.

For most of my life, I've been skinny, showing ribs. Even when I reached my full height, six feet, as a teenager, I only weighed 145 pounds.

As I aged, falling in love and therefore eating more, my weight gradually crept up.

My company changed to all casual days about five years ago. Instead of just having Casual Fridays, you could now wear jeans any day of the week (when a company does that, I think it should downvalue Fridays even more, to where instead of Casual Fridays we have Clown Fridays, everyone showing up with a red bulb on their nose, ruffled Bozo collars, and long, upward-curling shoes).

Because of the switch to all-casual, I haven't worn any of my suits in about five years.

The last time I wore a suit, I probably weighed about 180 pounds. Right now, five years later, I weigh about 195 pounds. I can't fit into any of my suits. And I have to wear a suit during my testimony.

I have to lose weight.

I love eating. I mean, I really love eating. Put a red, roast beef sandwich in front of me, lathered with mayonnaise, sprinkled with salt and pepper, or a huge, triangular slice of pizza, the type where the toppings droop the pointed tip down as you lift it to your mouth, or a heavy-in-the-hand, steaming cheeseburger, the hot moisture of it felt in your fingers, and I'm there.

I've always thought the way the whole eating/gaining weight thing works is upside-down. To me, it makes far more sense that the more you eat, the flatter your stomach should get, because you're exercising the muscles of your stomach more than someone who eats very little. It should be that if you see some guy with a washboard stomach, your first thought would be, "His grocery bill must be outrageous."

Anyway, I started counting calories. The thing about counting calories is that it's a lot like budgeting money. The electric bill is $400 this month, so that means we have to cut back on videos. That Orange Beef I chop-sticked my way through is 700 calories, so that means I'm having lettuce for breakfast. And just like you always seem to run out of money in a budget, you always run out of calories in a diet.

To increase the rate at which I lose pounds, I stated lifting weights again.

I actually enjoy weight-lifting. I stopped doing it a few years ago because it's so boring, but there is a pleasure in feeling every fiber in your muscles straining to get that barbell up where you want it to be.

It occurred to me during this process that I could write a humorous article about my losing weight, for something like Slate. Slate is an on-line magazine that solicits submissions. I've read a number of the personal experience articles they've published, and they're not that good. Mine would be much better. I could write it as if I were obsessed with losing weight, at all costs. I'd title the article, 'Losing It.' The article would end, "Mary, my wife, sat me down at our kitchen table. 'Rob, you've got to get off this diet. Food is all you ever think about anymore, all you ever talk about anymore.' I snorted. 'Baloney'".

But even as I thought about it, and started fantasying about it being published, and increasing the number of hits I receive on my site, and all the e-mails flooding in, I realized it wasn't something I wanted to do. I don't want to write humorous columns that exaggerate or lie about the reality of my life. So I didn't write the piece.

Yesterday, Friday, August 24, we received in the mail a stone carving of a curled cat with wings. We sent away for it, to place outside, in our garden, as a memorial on Elf's grave.

Elf was our first cat. We got her on November 30, 1990, and she died, in our arms, precisely one decade later, on November 30, 2000.

While she was alive, we had four cats: Elf, Rudo, Chirper and Sheba.

We bought Rudo, a black, long-haired cat, to keep Elf company while we were at work. Eventually, Elf, while still a kitten, went into heat. Each night we'd watch her lie stretched across the carpet, in the terrible, agonized state of being in heat, aiming her swollen, moist hindquarters, which she seemed to have dislocated from the tops of her back legs, at Rudo's sniffing nose. Rudo made a few belabored efforts at mounting her, but a moment or so after each attempt he'd drop his big front paws off her gray hips, snaking his nose back down under her tail, as if trying once again to locate the hole.

Needless to say, she didn't become pregnant. We had her neutered.

After we moved into our home here in 1991, we came down almost immediately with a terrible flu, that left us bedridden. During this time, an orange and white kitten, the color of a Creamsicle, started meowing at our back door. We eventually let him in.

His ears were cut up, and there was a wide gash in his hind leg. He had a big nose, which made his face homely.

He seemed slow, mentally, probably from months of living off the vegetables in garbage bags.

We named him Chirper, after a harmless creature found immediately outside the townships of the Sega videogame Phantasy Star.

Soon after we took him into our home, Chirper fell in love with Elf, who was slightly older than him.

Elf was royalty, a Gray Torti. Chirper wasn't. He was from the wrong side of the tracks.

He had a trick he did with Elf, lowering his nibbling fangs into the pink, inside membranes of her ears. She loved it. Her gray eyes would squint shut. Rudo, poor boy, would watch silently over the protection of his left shoulder.

And Chirper loved bringing her gifts. A glittering gold heart we'd hang on our Christmas tree, the silver wrapping from a cigarette pack, the top of a ball point pen.

Love can be cruel, though, and so was Elf. She'd retreat to the interior of a kitchen cabinet, curled up in sleep amidst telephone directories and supermarket cleaners, leaving Chirper waiting outside, on the white vinyl kitchen floor, face blank, for hours. She seemed to delight in spoiling his fun. We bought a round cat bed that had a plastic track running along its interior circumference, the track holding a ball a cat could endlessly chase around the track without ever pawing it out. Chirper loved chasing that ball around and around, never comprehending the impossibility of actually getting it out, but one day, Elf, having observed Chirper at play, maneuvered her hind end into the cat bed, spraying her orange horse's piss down into the track so that the ball became stuck in the glue of her dried urine, unbattable.

Chirper may have known she did this deliberately, to thwart him, but that didn't affect his love for her.

He'd be walking across our bed, meowing like a baby, but as soon as she walked in the room, thin and sickly, because by then she was dying, his eyes would roll towards her, still hooked, and hopeless. Whenever we wanted to know where Elf was, because she was good at hiding, we just had to look for Chirper. There he'd be, standing outside a cabinet door, or next to a chair leg, or in front of a pile of laundry. When she ate, he'd stand guard beside her, so the other two cats wouldn't try to crowd her.

After Elf died, the vet told us our cats might show some signs of depression. Rudo and Sheba didn't, but then, they never really liked Elf's position as ruler of the roost.

But we did notice a change in Chirper. His fur, which used to be wiry, got much softer. He spent more time alone, in the middle of the living room carpet, orange and white paws and tail gathered around him, face and eyes blank. He looked lost.

He still hops up into my lap. I was looking down at his face one day, while he was in my lap, and I said to Mary, "Do you know how his face looks now?"

She knew precisely what I meant. "Wizened."

And that was exactly the word I was thinking. He turned from a baby to an old man overnight, and we do think it's attributable to Elf's death.

Now that she is gone, he has more freedom.

So once more, after so many years, Chirper has returned to the game of batting the bright red ball around the track of the round cat bed, his orange and white face intent with the belief that some day, if his paw just bats it right, through one more hollow rattle, after all these years of trying the ball will finally be his, one last gift to give.

At three o'clock in the morning, that rattle is the loneliest sound in the world.