lately

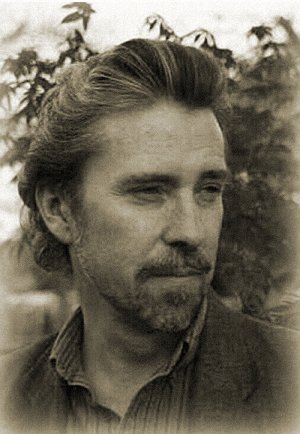

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2002 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2002.

we will never, ever know all that our mothers did for us

Mary started the second phase of her speech therapy this past Monday, November 4. Instead of six and a half hours a day, five days a week, at Pate Rehabilitation, in north Dallas, she'll now have one hour of therapy three times a week, at Baylor Hospital.

The reduced hours are an indication of her continuing improvement.

Baylor Hospital is located in downtown Dallas.

Like most downtowns, Dallas is a mess. One-way roads, detours for construction, intersections missing street signs.

We decided to drive into the city the Sunday before her first session, when traffic would be light, to figure out the route. A smart idea, because just before Baylor, someone had ripped up the entire street, wooden barriers with slanted orange and white stripes everywhere, rusted iron piping sticking up out of big holes in the concrete, some guy eating a sandwich on one of the corners.

That evening, we set our alarm for the first time in weeks.

Our appointment was at nine. We were asked to get there at eight thirty, to fill out forms.

We left our home at a quarter to eight Monday morning, both of us nervous about how the new therapy would be.

It was still dark outside, damp and cold, two weeks of rain, our CRV ticking on the wet driveway, Mary inside, as I rolled down the white front of our garage door, tiny snails attached to the paint.

Everything went fine until we got on I-35 heading into the city. Traffic was heavy, a few rain drops jiggling on the windshield.

Up ahead, at a speed twice the moving traffic, a car snaked behind and in front of the neighboring automobiles, fast, very fast, close to clipping a few bumpers, careening into the leftmost lane. Jesus, I thought. What a bad driver.

Which is when the car drove across the lanes, and I don't mean switched from one vertical lane to the other, I mean drove horizontally across all four lanes, back ends of cars jerking up, horns honking. Then it drove facing the four lanes of traffic, into the oncoming traffic, whipping around the cars, getting closer and closer to us.

After a circle around the speeding, brake-slamming automobiles and trucks, the car faced forward again, sped down the rightmost lane.

Mary and I looked at each other.

A miracle they didn't get killed, but even more of a miracle that with all that cutting in and out, driving sideways and backwards, let me repeat that, backwards, in heavy rush hour traffic, they didn't hit a single car.

I assume the way they drove wasn't intentional. Blow-out? No, because they were able to speed away. Drugs? I doubt it, because they handled the car fine afterwards. Their hands slipped off the steering wheel? They skidded? The crazy looping had lasted too long.

Just one of those incidents so out of the ordinary you wonder afterwards if you really saw it.

The suite we were supposed to go to inside Baylor, suite 100, didn't exist. As we made our second circuit of the ground floor corridors, a little old lady asked my help in opening a door to the outside. She was using an aluminum walker, like my grandmother used in her last years. The door opened on a small, rainy courtyard. Trees, pebble pavement, wet benches, red and white no smoking signs everywhere. She gave me a thankful smile, pulling out a cigarette. (Mary hasn't smoked in six months, because of her stroke. I smoked three packs a day, down now to one pack. I have a boxful of Nicorette gum I hope to chew someday).

Stopping a couple of people who obviously worked in the building, their stride said they knew where they were going, we found out the correct suite number. The atmosphere inside the suite was like a busy doctor's office. Promptly at nine, a woman opened the door by the reception desk, smiled at us. She gave her name, told us she would be Mary's speech therapist for her initial evaluation.

Once we were behind the door with her, in a large room where therapists were helping a mix of humanity with physical therapy exercises, she turned to Mary. "We need to go to the rear of this room, turn left, then turn left again."

The therapist hung back, as I did, because I knew instinctively this was the first test in the evaluation, to see if Mary understood what the therapist said, if she knew what "rear" meant, and "left", and could remember the directions as she made her way past the rowing machines, exercise bicycles, balance mattresses.

She did fine.

The three of us sat around one end of a long table in a large room. The therapist spoke to Mary for a minute, talking about Baylor's program, then asked Mary to give a chronology of what had happened to her.

Mary did fine, recounting the details of her stroke, her treatment at Pate, sometimes writing down a word she was having difficulty pronouncing, looking down at the written word on the sheet of paper, then being able to pronounce it.

The therapist seemed impressed by the level of recovery Mary has reached so far.

She showed Mary a thick stack of flash cards, each card a drawing.

Mary went through them without a problem. "Cat. House. Ocean liner. Pipe." The therapist stopped halfway through the deck, pleased.

On the way home, traffic much lighter, only a few fingers on the steering wheel, I remembered Mary said she'd like to switch from eating fruit for lunch to having a bowl of soup, now that the weather was getting colder. I thought of Campbell's, Progresso, remembered the dark, rounded pots of hot soup you could dip a ladle into at supermarkets, on the short sides of the salad bar. Which is when it occurred to me, Whatever happened to salad bars in supermarkets? The first time we encountered a salad bar was when we moved from California to Maine in 1982, surprised a state as produce-rich as California didn't have any, but they were everywhere in Maine supermarkets, and also everywhere when we went cross-country for three months in 1988. Mary and I would sometimes choose the salad bar for dinner, making our way around the long rectangular buffet with an opened square white styrofoam container in our left hand, which got heavier and heavier in the hand as we picked up the large silver spoons from the bins underneath the see-through plastic sneeze guards (lovely name) to add beets, marinated mushrooms, bean sprouts to our base of lettuce, teasing each other at the checkout counter as to whose salad weighed the most. Now there aren't any salad bars in supermarkets, at least here in Texas. Why did they go away? Was it something we said? One too many sneezes?

I mentioned last week Lady, our newest cat, who turned out to be pregnant, has been moving her five newborn kittens to different locations around our home.

What she's done lately, in their fourth week of life, is leave them alone, a huddled mass of different fur markings, for longer and longer periods of time, I suppose to wean them away from their dependence on her purring presence.

Each day, she lies on her side, to feed them, a foot farther out of the closet in Mary's workroom in which she last carried them, no doubt to gradually lure them out into our world.

Quite a few of the times she left them, she flopped down matter of fact in the next room, still a kitten herself, only a year old herself, to where they could see her across that wide stretch of white carpet, staring at them from the distance, I believe encouraging them to walk towards her, to strengthen their legs, their courage.

Here they come across the white carpet, in a wobbly wend towards Mommy. So small, so fragile, faces so big on their bodies.

We will never, ever know all that our mothers did for us.