BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

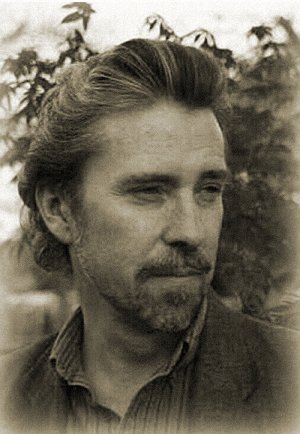

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Mars is Copyright © 2001 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to essays.

background on the essay

Almost every noble idea contains curled within it a horrible arrogance.

For space exploration, that horrible arrogance is something known as "terraforming", meaning impregnating other worlds with the green jism of earth life, so the planet so soiled can be habitable by humans a hundred years hence.

The error in this thinking is that if we infect Mars with Earth, we have forever, and I do mean forever, buried whatever uniqueness Mars has to show us underneath terrestrial moss, grass, and bushes.

We need time to coax from orange sand, swept gently aside with small paint brushes, the pretty symmetry of fossils, the gougings of tool use.

One prominent scientist wants to dump on our red planet hundreds of thousands of live cockroaches, because he believes this pest can best survive Mars' gravity, even though it will flatten and enlarge them. In the future, people will not shoot world leaders. They will shoot scientists.

mars

We won't ever get to Mars.

By 'we', I don't mean the human race. I mean you and me.

Back around the middle of the twentieth century, when it seemed like everything was about to happen, dependent only on grease and attitude, there was optimism that we, as a race, junior genius in farmland Nebraska grinding lenses, bald-headed janitor in New York City working out jumping champions for prime numbers, would vacation on other planets.

That's not going to happen.

The space program stalled a decade after it began, and even though it has been periodically revived, we somehow seem more concerned about putting a space station only a couple of hundred miles above us, rather than exploring out into where there are no man made objects yet. The Mars project has been hindered by a series of disasters, and even though it is thankfully moving forward, and someone from here will walk there someday, the possibility of one of us ever reaching up so high as to touch the finger of Mars will diminish even as it increases, we ourselves having grown too old by then to stretch that far, much like infinite halves of fractions added infinitely together, always getting closer to, but never reaching, the digit.

We have not arrived at the future the past predicted.

And what a wonderful future it was, that never happened.

I was taught by nuns. One day, the nun assigned to my class wheeled in a television set. All of us kids twisted our heads around, watching over our shoulders, lifting our little asses off our wooden one-piece desk seats, as she, bent forward in her black robes, black shoes digging in, wheeled the TV under one of the high windows at the back of the class.

We could not have been more astonished, a TV in our classroom, than if she had wheeled in a Cyclops.

She gave us the briefest smile, then continued teaching, but now from the back of the class, frequently consulting her black wristwatch.

After about fifteen minutes of unbearable mystery, she consulted her black watch a final time, stood with her black back to us in front of the screen, blocking us from seeing, and snapped on the TV.

It was May 5, 1961. 9:30 in the morning.

We watched this old, black-robed woman's bent back, flicking looks at each other.

When she turned around, letting us finally see, Walter Cronkite, a well-liked television news announcer, was talking. She twisted the sound up, and allowed everyone to slide their school desks forward. She talked over Walter Cronkite's modulations in her high, trembling voice. "An American is going to go up into outer space today in a rocketship, and then land." A black and white image of a real rocketship appeared on the screen, tremendous billows of smoke starting to rise out sideways from under its base. We heard an unseen man on the television start counting backwards.

"Heads down! We're going to pray for the safety of the man on board, Alan B. Shepherd, Jr. Our Father, Who art in Heaven..." We all tagged along, sing-song, with her recitation, but all our eyes, and hers, were glued to that set, to that small screen, to the immensity of the smoke pouring up, until three, two, one, like the biggest magic trick, we saw the great metal finger levitate a few feet off the launching pad, amazing in itself, then thunderously rise, jerk, rise, climb in a deafening ascent, the loudest voice, smoke dripping off, to the black and white clouds and through, leaving all of us behind forever.

Fifteen minutes later, Shepherd returned to Earth, as planned, a little over 300 miles away from where he had been launched.

After that, our collective imagination saw the future as immense delicate cities filled with flying people whizzing above and among the structures, who needed only to tilt back to escalate up to the domed cities of the moon. Someday, we would be Jetsons. Someday, We, but not you nor I, will.

After Shepherd's flight, as man's first small steps across the 'final frontier' continued, as excited as we all grew during that decade, culminating with the first moon landing at decade's end, there was little impatience with the pace of our accomplishments. We were speeding face-forward into the future, hair blown back, cheeks acquiver from the G-force. Everyone was young, because I was.

Now, however, after a series of disasters, some of them due to NASA's own sloppiness, it appears likely the earliest any human will set foot down on Mars will be 2020.

I'll be seventy years old then.

I may not still be alive. I may not live to see what was promised to all of us that day in May, 1961.

If alive, I'll look remarkably different from the little crew-cut boy in the white shirt with blue-grey tie who saw that first lift.

Back then, only ten years old, "my whole life was ahead of me".

During the nineteen-sixties, I went from ten to twenty, that most profound and unsettling of all human leaps. In high school, while the teacher at the front of the class droned on, I'd amuse myself by writing down what I then believed would be my future oeuvre, taking the greatest care to draw in dark blue ink at the left edge of the white, green-lined page the rounded numbers of each future year, and at the right side of the page, my accompanying accomplishments. This novel published then, followed by that play, one or two story collections. Some years I'd allow only one entry, which signified to me, the sole reader of this list, that that year's work would be particularly weighty, taking, as it would, all of twelve months to produce. As I recall, 1973 was a particularly busy year in my projected career as a writer. I think I had two novels listed on the right hand side, as well as a story collection, a book of essays, and several movie appearances. I'd debate with myself very carefully the placement of each book. Should I really commit "Novel About Group of Friends Who Discover an Unpublished Manuscript by a Favorite Writer, and Get It Published" only five years into the future? Shouldn't I probably write "Novel That Takes Place On A College Campus" first, so that I'd have some time to hone my craftsmanship for the greater talent test of the undiscovered manuscript novel?

The list got me through high school. It did, because it promised happiness ahead (what better way to control your fear of failure in your personal future than to document your successes in that future before they even occur?)

When I was eighteen, I watched Neil Armstrong first step down onto the moon, the black and white image wavy and seemingly underwater, while sitting naked in a chair in a hotel room in Greenwich, Connecticut, drinking vodka straight from the bottle, a nude girl sleeping on her stomach in the bed behind me. I felt powerful.

In the years that followed, and follow they must, one dream after another of mine went away. I haven't become a famous novelist, I never made a series of brilliant, low-budget movies, I never found out what it felt like to plant my feet wide apart on a wooden stage and sing into a microphone, Adam's apple vibrating, tens of thousands of my fans screaming my name, tossing in front of my swagger, white-twisted joints. In my earlier decades, I sometimes wondered what it would be like, to be Vladimir Nabokov, or David Lynch, or David Bowie.

I never found out.

There are those among us who reached their dreams. We touch them only with a fingers-spread hand planted on a newspaper headline or television screen, but there they are, at this party or that, surrounded by their breed, traveling to the most beautiful, green spots still left on our Earth, eating breakfast, on a terrace with waterfall views, talking to a princess, a famous old person.

I've been informed of the lives of famous people for so long now that in some ways it almost feels as if I myself lived that life, simply because the amount of details provided make it so easy to imagine I can enter what it must have been like to be Mick Jagger in mid-nineteen-sixties London, smirking, white-scarfed, in a noisy club; William S. Burroughs in Algiers, in bed with friendly brown-limbed Kiki, first fore-feeling what would grow into Naked Lunch; Robert DeNiro with a curled-back script in his lap, looking off into space, finding within himself, with a shoulder twitch, a down-turned mouth, a scrunch of the small, flat muscles under the eyes, Jake Lamotta.

We live nearly all our lives in our minds, jolted out only by car crashes, an unexpected sentence, a truly great hamburger.

In our minds, no god is taller or wider than vicariousness.

But it's good we never do all we can imagine, and so often, far less. It's good our fancies are brought down by the drag of what actually happens, to make it difficult for us to too completely perfect that which is not real. Our great consolation, for many of us, is an ascent to Heaven, where what could not be done, can be, or can be let go. It wouldn't be good to some day be able to imagine a future more desirable than Heaven, because death would then truly be a descent.

Allow me now, in my failed dreams, and your failed dreams, and our nation's failed dreams, and our present world's failed dreams, to be vicarious.

This essay goes out, not to us, but to Us, to those in the far flung future for whom interplanetary travel will be, if expensive, if rare, if stomach-flipping, if even once-in-a-lifetime, available. I imagine you, my distant reader at the rim of my fame, hunched, looking down at your blue boots in the red and orange dust, slowly straightening your bulky-suited body in the unfamiliar gravity, your stereo breath in your ears, perambulating clumsily across the sandy bottom of an ocean fifty million miles deep, looking up, like the most frightening look down, at my little blue and white planet from the past. I hope it stuns you, where you are. I hope you feel the boil of diarrhea in your bowels. I hope you take one moment to silence yourself from the routine, perhaps even inane, radio chatter to think one word to yourself, the thrill of it as slippery and challenging as a fish flipping through your fingers.

Mars.