BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

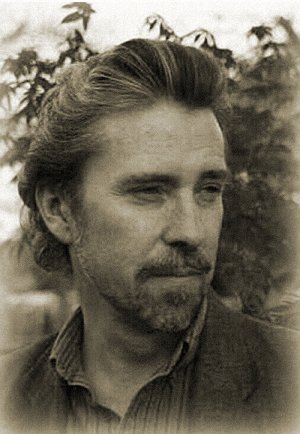

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Sea Scallops in Cream Sauce is Copyright © 2002 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to essays.

background on the recipe

Mary makes this dish whenever her dad, Joe, visits.

The cream gives the scallops a nice, rich flavor, the fresh basil keeping the sauce from getting too rich.

One of the best parts of the meal, once you've eaten all your scallops, is using the french bread to mop up all the cream sauce.

friends before food

People are fussy about what they put in their mouths.

I know people who have never tried lamb, never ordered Chinese food. I knew one woman who was normal in every way except she had never, in her fifty years, ever eaten pizza. The look of a pizza, its circularity, its chaos, turned her off.

This aversion to certain foods is particularly strong when it comes to seafood.

Seafood is the last 'wild' food left to us. Caught rather than raised. Most people are afraid to cook it, partly because they don't know how to tell when it's done, partly because the particular seafood they're preparing, such as lobster or shrimp, is an entire animal. Animals look very untidy.

Probably the most fearful of all seafood is the oyster. You pry apart its dreadfully unsymmetrical shells, still cold from the ocean, it struggling within to stay shut against your sliding blade, and slip into your mouth something still alive, the wonderful taste of rawness and the sea's brine slicked on your lips, while you laugh at your dining companion's sly joke, glancing over the flickering candles around the restaurant, hair perfect, for once, realizing you truly can do anything you want to, tonight.

Scallops are the perfect dish for people who find oysters disgusting.

Although oysterish when their shells are pried open, all sorts of dark colors and raw slackness revealed, scallops are remarkably tidy in the form in which they're offered in supermarkets, and in fact I believe there is no other food which is so absolutely free of any vestiges of animalness as a pure, pearlescent lump of scallop. In this regard, the scallop is so completely anonymous, so devoid of any suggestion of a body, that it is the sea's equivalent of the boneless, skinless chicken breast.

Some seafoods are like eating a hitchhiker. Scallops are like eating a cousin.

As a bonus, because the scallop is pure meat, there is nothing to throw away.

Scallops come in two sizes. Bay scallops and sea scallops.

The bay scallop, existing close to the coves of hillside fishing villages, a pub in the center where the men and their women gather to drink and listen to jukebox music between trawls, as has been often depicted in movies, is a meek, mild bit of meat about the size of a swollen pencil eraser, pale in color. You could eat dozens of them and not feel full.

Vessels that venture farther out over the swells of the dark green ocean, to where the ridge of land slips away behind the horizon, and nothing is left of the familiar earth except the sun, drop nets over their sides, and bring up the much more coveted sea scallop, a heavy in the hand treasure about the size, shelled and cleaned, of an unbaked biscuit, and the same color, flat on top and bottom, with rounded sides.

This recipe calls for sea scallops. Although I don't suggest buying shrimp in supermarkets, because of the heavy chemical saturation they're immersed in to embalm them and therefore preserve their shelf life (see Deep Shrimp for more details), scallops are generally safe to buy almost anywhere, because since they are pure meat, they last much longer.

Although most markets advertise fresh scallops (and fresh everything else), in fact almost all seafood is shipped to the market frozen, as it should be (it's frozen on the shipping vessels.) The scallops you see in the glass display case, thawed and wetly piled atop each other, may be anywhere from one day to several days unthawed, depending on that market's turnover rate. For that reason, you're far better off asking the 'fish monger' (who these days has probably never been near an ocean), to sell you the frozen scallops he has in back. He or she may hesitate to do so (they want to sell the thawed scallops first), but if you politely insist, they'll almost always agree (although you may have to buy the frozen scallops in whatever unit they're shipped, usually in five pound bags). The advantage to buying frozen scallops (or any other frozen seafood) is that you're buying food which is of a much higher quality, since it's never been thawed. The key to buying seafood is not to buy seafood that's never been frozen-- that's virtually impossible, and in fact probably not desirable-- but instead to buy seafood that's never been thawed (until you thaw it).

You should treat any seafood you buy as if it were ice cream. In other words, keep it constantly cold. If you're doing a week's shopping, buy your seafood last, not first, so it's not sitting in your cart at room temperature for half an hour. Mary and I, whenever we buy seafood, bring a cooler with us, with ice inside. As soon as we get to our car, we put the seafood under the ice. Some markets will pack your seafood purchase for you in a small bag of shaved ice, which is ideal, but the practice seems to be getting rarer and rarer.

The scallops you do buy, if you buy them fresh, should be glistening and sweet-smelling. If they look dry, or if the meat appears to be separating, little striations across its surface, don't buy them. Make something else instead. If you buy sea scallops frozen, they should look like they're individually frozen in the bag. They may be stuck to each other-- the bag may not rattle if you shake it-- but they shouldn't look like one solid lump.

And they shouldn't be pure white. They should have a subtle orange tinge to the meat. Otherwise, you may be buying a cheap fish whose sides have been punched with a circular cookie cutter to approximate the shape of real sea scallops. Sea scallops come in different sizes and shapes, just like people and words. If all the scallops behind your fish monger's glass counter are identical in size, walk away. Selling punched-out circles of a cheap fish as sea scallops is still practiced in quite a few markets.

To make Sea Scallops in Cream Sauce, you'll need:

One and a half pounds of sea scallops

Flour to coat the scallops

Salt to season the scallops

Black pepper to season the scallops

2 tablespoons olive oil

3 tablespoons butter

6 plum tomatoes

2 tablespoons fresh parsley

2 cloves of garlic

6 heaping tablespoons of fresh basil

Three-quarters of a cup of heavy cream

One loaf of French bread

This is a delicious dish. The cream sauce has a lot of flavor to it, and the strips of plum tomato and fresh basil give it a festive look. The basil adds a nice shading to the taste.

To prepare, wash the scallops thoroughly, to remove any sand that might be creased into their white flesh. Then wash them thoroughly again. Nothing spoils a scallop dish more than the grit of sand between your teeth.

Wrap the wet scallops in paper towels, gently tumbling them around within the paper like fat blind babies, to dry them.

Put a quarter cup of flour in a paper or plastic bag, then drop the heavy scallops inside, using your hand to close the top of the bag, like shutting off air to a throat, tossing the scallops sideways until they're lightly coated with the flour.

Heat a skillet to medium heat, and once it's reached that temperature, place a tablespoon of olive oil in the skillet, and melt in that oil two tablespoons of butter.

Once the butter is fully melted down to yellow bubbles, gently place the floured scallops into the skillet, sautéing them on both sides until they're cooked. Since scallops cook quickly, this should only take a minute or two on each plump side.

Don't crowd the scallops in the skillet. You may have to cook them in two or three batches. Since scallops come in different sizes, remember that large scallops will take slightly longer to cook than medium scallops.

Remove the cooked scallops to a plate, and season them with salt and pepper. Seafood is known for "taking a lot of salt", but be careful not to sprinkle them with too much salt at this point. If you eat raw tomatoes, use about as much salt on a scallop as you would on a tomato wedge.

Add the remaining olive oil and butter to the skillet, and while the butter melts, slice the plum tomatoes into half-inch slices, and add to the skillet.

Rinse the fresh parsley under cold water to get out any grit, mince two tablespoons worth, and add to the skillet.

Mince the two cloves of garlic, and add.

Cook until you smell the aroma of the garlic, under one minute.

Pour the heavy cream into the skillet.

Reduce the cream, until it coats the back of a wooden spoon, about three or four minutes (or longer. Don't go by minutes. Go by how long it takes for the cream to coat the back of the spoon).

Julienne the fresh basil (cut the basil leaves into thin strips about a half inch wide), and add to the sauce.

Put the scallops back in the skillet. Bathe with the sauce and let simmer about two minutes.

Taste the sauce at this point for seasoning. You may find you need to add a little more salt.

Serve the sauced scallops in bowls, with French bread passed around to mop up the pink and green sauce in which the scallops are immersed.

Faces floating above candlelight, hair and eyes and laugh lines, talk about the ocean. Talk about wooden ships a thousand miles from shore. Talk about aromatic, seaweed-clotted nets hauled aboard, and the catch sunk within the net, slapped down on the deck, still flapping as the sea waters slide across the boards.

Talk about small islands.